Countering the Master's Maps

Changing our mental maps is the first step to new forms of ownership, and a new relationship with land and place

DISCERNING A PATH ON PROPERTY: REDISTRIBUTE OR DE-COMMODIFY?

When I began writing Unsettling, I expected to do a lot of reading on land reform. Specifically, on land redistribution as it has taken place in other countries, and generally, alternative forms of land tenure ignored by the U.S. Basically, I expected to hang out with some heavy stacks of very dry volumes on economics and history. That willingness to let my eyes get all glazed over staring at figures of land transfers listed in hectares was driven by a general thesis that the concentration of land ownership—especially concentration of corporate ownership—is a major problem with negative effects for just about everyone. When the land is owned by a wealthy few, housing costs go up for everyone else. The food system also becomes more centralized, and more fragile as centralization tends to lead to monocropping; food costs go up and can be—in moments of disruption such as in the pandemic—less reliable. There is less public or common space and hence less public or common culture. Centralized ownership by corporations also tends to be profit-focused and thus antithetical to most conservation or stewardship goals. Both redistribution and decentralization of land ownership hence seems to me to be one of the most fundamental and systemic forms of change one could engage in. So I had questions like: If radical land reform can happen elsewhere, why not here? What has it looked like in other countries and how might it play out here? And also, Are there strategies for land reform that could avoid the massive amounts of violence that often accompany redistribution efforts? Can we not only avoid such violence but heal wounds caused by past harm by linking redistribution or reform to efforts for reparations and repatriation?

Big and thorny questions. Only it quickly got even thornier, as a set of apparent conflicts between the aim of land redistribution—for the purpose of general social good or for the purpose of addressing racialized inequality via reparations—and the aim of repatriation or rematriation to Indigenous communities swiftly came into view. You can’t just go about redistributing land that’s not rightfully yours now, can you?

These additional considerations have led me to pivot away from a focus on land redistribution as it has been historically enacted (via state appropriation or the breaking up of large landholdings then redistributed to smaller private owners) and to a focus, instead, on efforts to decommodify, or “de-propertize” land. This would seem to both address the concerns that led me to thinking about land redistribution in the first place and aid the restoration of Indigenous governance and stewardship, and perhaps even resolve the conceptual tension created historically in which the dispossessed find themselves bound to use the thief’s concept of ownership in order to receive back what has been taken.1 As I see it, decommodification immediately takes down the “private property, stay out” signs that prevent access to ancestral lands, sacred sites, gathering spots and other important areas; it also opens up the door to governance and stewardship claims beyond those afforded by current property laws. Hence the quest for existing precedents that might show us backdoors through which to begin decommodifying the land.

MAPPING AS THE MASTER’S TOOLS?

Yet I’ve also come to see that there’s another important pivot—or at least an important stop to make along our way—before progressing on to evaluating policies and case studies for decommodification or alternative models of ownership. This one is necessary because much of the nature of property law exists, not so much in any legal code or regime of enforcement, but in our minds. Law and culture are always intertwined, shoring one another up. Our unexamined beliefs and practices about private property help the ever-expanding laws on private land ownership seem natural and normal, when the truth of the matter is that a good deal of work and violence have been exercised to put them into place. Finding models of shared ownership, or of private-to-public land transitions, doesn’t necessarily tell us how we undo the mental frameworks that encourage us see the physical world through the lens of ownership and commodification in the first place. How do we begin to transform such widely held preconceptions?

One place to start is with our maps. When it comes to land (in comparison to other social relationships), our mental maps are often quite directly derived from maps as objects, be they physical or digital. We face a question then: do our maps, as tools we opt to use, serve us in holding the kinds of relationships with the land that we wish to hold? Do our physical maps create within us the mental maps we wish to navigate by? Are they effective in helping us move towards decommodification or decolonization?

My guess is that if you’re already someone who uses your time to dwell on such things, your answer to that question is likely to be either a) a lengthy qualification about how such tools can harm but are also useful and how we need to figure out methods by which to ameliorate the harms while reaping the benefits, or b) an easy and quick and forceful “NO.” Those of you on the latter team definitely have a lot of evidence to marshall in your favor. Maps, after all, were clearly a necessary tool of U.S. expansion and colonization. From the Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Public Land Survey System, which furthered settlement in the country’s interior by measuring it out, to the General Land Office (the predecessor of the Bureau of Land Management) and surveys by Lewis and Clark and beyond, to later expeditions in the late 19th century by the United States Geological Survey—which sought “to inventory” the nation’s lands and resources therein—mapping land was definitely an activity of empire-building.

Team “NO” might also be tempted to trot out the well-worn Audre Lorde quote “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house” as a little decorative sprinkle on top of their mound of evidence there. Permit me a detour here to share some thoughts about that quote, as I think it will serve us not only today but also in future discussions to more carefully think through it. I consider and wonder about it often, given that we commonly find ourselves in these times forging a world that is harmful to ourselves by use of tools that we do not always have a great deal of choice in using. Is Lorde right? Can we only construct a new world—or chart a new course—with tools we must also design ourselves? Or can we use those the master has left lying about?

Like what you’re reading? Show your support by becoming a subscriber:

Lorde’s quote is a good example of the curious process by which a well-worded quip can turn into an unquestioned belief or an unexamined value. This is now a daily collective practice via social media memes, with various values constantly overturned by the next pithier or more cutting phrase poking at the unstated assumptions of the prior offering. Such habits predated the internet, however, even if they moved more slowly then, as “the master’s tools” did. Its very meme-ability is what leads to its adoption; the concept seems intuitive, the logic obvious to many—if these tools caused injustice, surely we shouldn’t use them—in such a way that it does not require us to pause and consider all the beliefs we are bringing along in this disavowal of the master’s toolkit. Are we giving up agriculture? Computers? Only those tools that allow him to be a master? Which ones are those, exactly? The quick disavowal of dominant tools and institutions by those who keep Lorde’s quote in easy reach for performative mic-dropping skips over these questions that are neither simple nor rhetorical.

Acknowledgment of the context of Lorde’s essay is important for avoiding oversimplistic application of her ideas. The piece serves to call out white feminists at an academic conference for using certain tactics of oppression—those typically exercised by men against women—against Black feminists and lesbians. She cites in her examples the failure of the conference organizers to include those with different experiences in their planning. She is addressing a particular social setting, and she makes no pretenses to setting up some more generalizable principles of a feminist approach to technology or tools. This in itself might caution us against overly broad use. Nonetheless it’s possible that Lorde’s reasoning in the paragraphs leading up to the “master’s tools” quote gives us something with which we can work on a more general basis, as we think about the use of tools to shape the world for better, including our physical and mental map-making tools. There she describes the failed inclusivity of the conference planning as a result of an improper target, which she sees as “the mere tolerance of difference” rather than a true appreciation of the differences between people and all that difference might offer. She writes:

Advocating the mere tolerance of difference between women is the grossest reformism. It is a total denial of the creative function of difference in our lives. Difference must be not merely tolerated, but seen as a fund of necessary polarities between which our creativity can spark like a dialectic. Only then does the necessity for interdependency become unthreatening. Only within that interdependency of different strengths, acknowledged and equal, can the power to seek new ways of being in the world generate, as well as the courage and sustenance to act where there are no charters.

Within the interdependence of mutual (nondominant) difference lies that security which enables us to descend into the chaos of knowledge and return with true visions of our future, along with the concomitant power to effect those changes which can bring that future into being. Difference is that raw and powerful connection from which our personal power is forged.2

The way I read Lorde, forced homogeneity is the master’s real tool. Which gives us a clue as to what kind of geographic tools and maps might be more or less useful in aiding us to change our relationship to land. Does it allow for the different, for variation, for the outright weird? Does it allow for different kinds of people as well as different kinds of places? By “allow for,” I mean, does it encourage us to see and seek out and appreciate difference—to be in relationship with it—or does it flatten it, hide it, help us look away from it?

AN EXAMPLE OF THE MASTER’S MAPPING

Modern mapping, one could argue, is premised precisely on denying difference, on forcing homogeneity in the name of creating legibility.

Earlier this year, I wrote about the establishment of the U.S.-Canada border, as part of the Borderline Histories series. I recently revisited some of the documents referenced in those posts, including the Oregon Treaty of 1846 and the Treaty of 1818, in light of returning to Salmon Nation, and in an attempt to consider what it would mean to honor the treaties here. But these are the types of treaties that make the call to “honor the treaties” seem like a ridiculous demand: they are made between the United States and Britain alone, with no mention of the many peoples already at home throughout the Oregon Territory and how they fit into the future of the region. Britain’s goals, as is true of much of their colonization efforts globally, is the protection of corporate property; there are separate articles naming property rights for the Hudson Bay Company and its subsidiary the Puget Sound Agricultural Company (created, as it happens, to help HBC sidestep legal rules limiting their monopoly in the region to the fur trade). These are treaties intended to help two white-led nation-states and their affiliated corporations more congenially continue their respective efforts at extractive economic growth. It is only after these treaties that the U.S. will sign agreements with the many tribes within the region. It is in the 1850s, for instance, that the treaties with the tribes making up the present Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde were signed.

The negotiations leading to the U.S.-Britain treaties instigated further surveying and mapmaking of the territory. Note once again that it is the mapmaking itself that allows them to stake their claim; they know the land so poorly to begin with that they cannot actually fully exercise ownership without going and measuring it. But here’s a fact I picked up about the Treaty of 1818, that I missed the first time around: as you may know, that agreement sets the dividing line between Canada and the United States at the 49th parallel (already, a mapping tool used to standardize the entirety of the globe). Why the 49th parallel? Why not a description of other natural features, as had previously defined the border after the Louisiana Purchase? Because the watersheds were considered too darn complicated to accurately map, that’s why. Rather than adhere to the contour of the rivers, they chose an abstraction to mark the border.

In other words: reality was too difficult, its form too different from what our tools wanted to see, so we took a big sharpie marker and drew one big straight line and called it fair.

COUNTER MAPPING

One might say that, effectively, most private property borders are the results of such simplistic and brazen line-drawing. From this we might gather that one way to begin changing our mental conceptions of property is to find ways to see the land under us and around us without all those thick marker lines invisibly written upon it, cutting watersheds straight in half.

Alternative mapping projects have grown popular in recent years, but frequently they take the format of superimposing new names or knowledge over those same inked-in boundaries with which we are familiar. (Not knocking these projects—I’m a fan of Decolonial Atlas and others, and most don’t do this exclusively.)

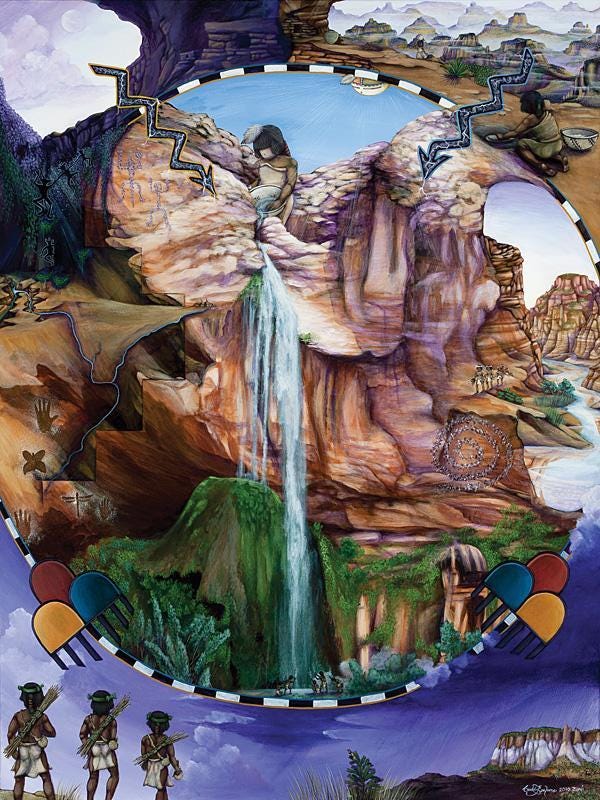

Somewhat different in kind, however, are the maps produced by what Zuni tribal member Jim Enote calls “counter mapping,” a project he initiated while director of the A:shiwi A:wan Museum and Heritage Center.

Enote was profiled both in print and film by Emergence Magazine in 2018. The article—which includes many images from the A:shiwi Map Art collection at the A:shiwi A:wan Museum, so head over there to see them—describes how the Zuni people experienced map-making at the hands of the U.S. government as a tool of dispossession. In the film, Enote reemphasizes this point, saying: “More lands have been lost to Native peoples, probably, through mapping, than through physical conflict.”

Discussing the maps made not only by governments but by entities like Google, Emergence author Chelsea Steinauer-Scudder writes:

Such maps are widely assumed to convey objective and universal knowledge of place. They are intended to orient us, to tell us how to get from here to there, to show us precisely where we are. But modern maps hold no memory of what the land was before. Few of us have thought to ask what truths a map may be concealing, or have paused to consider that maps do not tell us where we are from or who we are. Many of us do not know the stories of the land in the places where we live; we have not thought to look for the topography of a myth in the surrounding rivers and hills. Perhaps this is because we have forgotten how to listen to the land around us.

The “counter maps” commissioned by Enote and a committee of Zuni elders, council members, and religious leaders are not based in route-finding, and they don’t presume a universal audience. Instead they tell Zuni stories and history, not all of which are meant to be known to just anyone. Steinauer-Scudder sees this as potentially useful:

To outside eyes, what is perhaps most haunting about the Zuni maps is that they confront us with not-knowing. They present us not only with the stories and myths that we are not privy to in the Zuni worldview but also with the disorienting realization that many of us have forgotten the earth-based stories and myths of the places of our own, or that we never had those stories to begin with… They suggest that the stories that are particularly rooted in the land can only be discovered by taking the dedicated time and attention to encounter the land itself—over long periods of time, through many seasons.”

And this is how Enote discusses his own wayfinding on Zuni land:

“For me, the whole landscape around here is home. I have patterned languages that help me to remember how I get from one place to another. I go to my field in the summer. I collect wood in the fall and winter. I may be pinion picking or going to collect tea. . . . This whole constellation of what makes up a map to me has always been far beyond a piece of paper.”

I see in counter mapping an example of mapmaking that fits Lorde’s notion of moving beyond mere tolerance of difference and choosing instead to see difference as a strength that allows interdependence. These are maps that are happy to show the Zuni’s unique relationship to places, with no apologies for how different that may be.

While Lorde was primarily speaking about human social interdependence, the application to the more-than-human seems clear here as well: we cannot really know a river if we cannot tolerate its refusal to live and run beyond our straight lines, and we will fail to see our interdependence with it as well. The mapmaker who finds the watershed too messy to survey will not have a healthy interdependent relationship with water.

The mapmaking tools we have today are obviously more sophisticated than the surveying equipment of 1818. Satellite imagery and other processes might allow us to capture natural features in a more careful manner, meaning we don’t need to shrug our shoulders and resort to imagined lines on an idealized and flattened version of the planet. Yet greater accuracy (in some forms) aside, does relying on the maps we use every day to get around hinder or help the project of changing our relationship to the land? Does it further commodify land as property, or does it “de-propertize”?

I have a few stories of attempts to get by without our standard navigational tools and with a little less regard for property boundaries than I might normally demonstrate. The results: mixed, and likely to amuse, so keep an eye out for upcoming emails if you want a good laugh. In the meantime, while my reading list has changed, I’ll keep on plugging away on the questions driving Unsettling. Have something you think I should read and share back on? Don’t hesitate to reach out and send your suggestion to unsettling@substack.com.

Until next time,

Meg

As theorist Robert Nichols has noted, it is “a curious juxtaposition of claims that often animate Indigenous politics in the Anglophone world, namely, that the earth is not to be thought of as property at all, and that it has been stolen from its rightful owners.” Nichols book Theft is Property! Dispossession and Critical Theory takes on this seeming contradiction and analyzes how “dispossession merges commodification (or, perhaps more accurately, “propertization”) and theft into one moment.”

From “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House,” in Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, p.111-112