Am I Home Yet?

on moving and finding new names for familiar places

What does it mean to belong to a place, to call a place home?

I have been asking this question nearly my whole life. Which might be obvious to anyone who has ever queried me with the seemingly banal “Where are you from?” and found themselves subject to a litany of place names, or a long tale of how one adventure took me to one place to another and then funny enough this happened and now here I am. The logic of these stories feels questionable no matter how true the facts: I live in Seattle because of an October snowstorm in the Goat Rocks and an unplanned encounter in a bar. Or, I live in New York because I saw a flyer on a telephone pole in Chicago five years before but also because my heart broke in L.A. and I needed a job. I don’t ever let people have it easy when they ask about origins or even one’s place of residence. Too many of us have been displaced, by obvious and violent forces or by the more subtly corrosive effects of markets, for anyone to think this an easy question to ask these days. Many often presume choice is why people are where they are, but chance and a short set of chips with which to try one’s luck are equally likely explainers in our current world.

Myself, I’d already lived half a dozen places by first grade, and though the pace would slow a little we relocated often enough that I went to two different middle schools, two different high schools. In college I would learn the strange effects resulting from assumptions about where one “was from” after I was branded as “from Missouri,” a state in which I had lived barely two years. It was just the last place I had been, the last place where my parents had packed me up and taken me.

In recent years, though, I’ve begun questioning my own self-narrative about my family’s itinerancy. Though we switched neighborhoods and houses more than once, the bulk of my school-age years occurred in the same city. What if I had roots that were deeper than I realized, just simply long neglected?

My adult life has been marked by much of the same wandering pattern of my youth, school or partners or jobs or just the possibility of new experiences all pulling me this way and that across the country. The last year might be the apex of that pattern: my partner and I became one of those remote-working, wandering couples you might have read about, roaming areas of the West and Southwest. Six weeks is the longest we were in any one location. But we always knew there would be an endpoint, and a major one—not just the end of our travels, but of the relationship as we had known it. Here too we fit some sort of new cliché: the pairs who found the isolation of the pandemic gave them time for long-delayed conversations, a chance to recognize that our paths, ultimately, were leading in different directions. We broke the stereotype somewhat by choosing to weather the times together, rather than separate in some rush and fear of an indefinite quarantine with one another. We do like each other, after all; that we knew, even if we didn’t know much else about how to work things out. Our parting of ways thus became a postponed event, like much else in the past year. Meaning I had some time to consider: where, absent some easy justification like a new job or a partner’s job, should I be? Where might I belong?

It seemed fitting, in this year in which I have begun to write Unsettling, to return to the one place where there might be hidden roots sustaining me in some unexamined way, and so I made a choice to move to the city in which I turned from a child into a teenager, before my family once again loaded up a massive moving truck and headed back further east. Only I’ve come to see that I’m not returning to this particular city, so much, as to a region that I’ve been circling and crossing even more continuously, not only in my youth but in more recent years as well. I haven’t typically understood these various visits and stays to be tightly connected because our usual way of talking about places is set by smaller governmental boundaries, by municipal borders and state lines. According to those ways of talking, I’ve been in different places; I’ve been wandering, not rooted; relocating, not simply migrating within a unified territory. But that’s not really how I understand my own personal movement. There’s some sort of unspoken unity that links the coast of Humboldt County in far northern California with the high reaches of the Cascades in Washington and all the Oregon rivers I’ve crossed and re-crossed in-between. Where I’m landing now, in the city of my youth, is a point on a map from which I can create a thru-line to all these other places.

As I’ve been in the process of moving, unpacking and sorting through boxes held in storage this past year, I have come to realize my discontent with the name given to that point on the map, its unhelpfulness in placing me or orienting me to where I am or might belong. I can see when I tell people where I have moved that there’s little in its name that points to its connectedness, to the broader relations of the region; there’s no story there. I began to ask a new question: what if I haven’t known where home is, not because there isn’t some sense of belonging, but because no one ever taught me its real name?

What names are useful for places?

One time, at a workshop, I attempted to introduce where I then lived in a manner that did not rely on place names connected to the governing apparatus of the city—street grids, say, or official neighborhood designations—and instead focused on natural places. “I live north of the channel that connects our two lakes, on the hill just beyond the ravine, not quite at the top, near a long line of chestnut trees.” I remember being rather pleased that I could place myself this way, and I could see people who were puzzled at first slowly comprehending where exactly I was describing. Yet even so I didn’t get the sense of any broader understanding about my motivations for doing it. (Which seemed odd, in a way, in an anti-oppression workshop focused on solidarity with immigrants, where one might have expected playing with and redefining the boundaries that make up our mental geographies to be the order of the day. Though I get it; I was also being a little long-winded.) But I thought about this attempt when I was reaching for some other way to name my once-and-current place of residence. That is the type of grounding, of orientation, that I am seeking, in order to know if I am home.

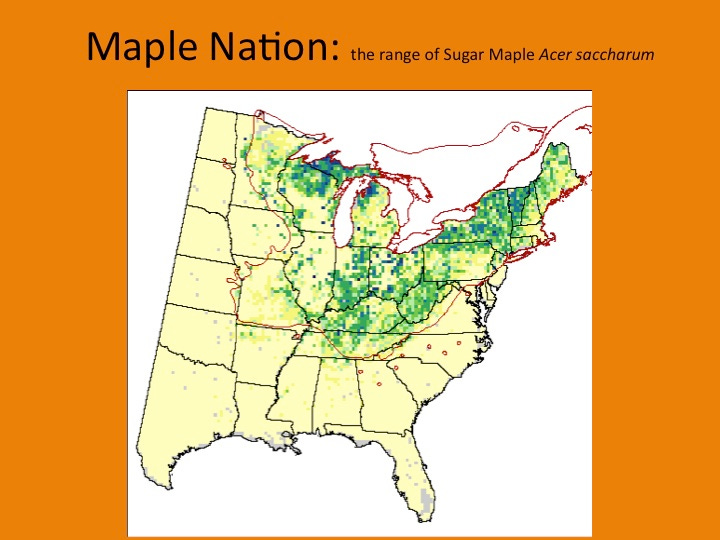

I have heard whispers of other names at moments throughout my life that could maybe provide such a grounding, but I was having trouble hearing them again in all the prep and planning of making a move. Yet somehow I knew that I could pick up Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass and hear it spoken clearly to me. My copy had been sitting safely tucked away this last year, but by this last weekend was already unpacked, on a bookshelf and easy to grasp. I picked it up and and flipped through, landing on her essay “Maple Nation: A Citizenship Guide.” Certainly the title suggested I might learn how to belong somewhere by reading it. Could it tell me also how to know it, how to recognize it?

I began reading, and soon had the place name that I sought staring me in the face:

There’s a beautiful map of bioregions drawn by an organization dedicated to restoring ancient food traditions. State boundaries disappear and are replaced by ecological regions, defined by the leading denizens of the region, the iconic beings who shape the landscape, influence our daily lives, and feed us—both materially and spiritually. The map shows the Salmon Nation of the Pacific Northwest and the Pinyon Nation of the Southwest, among others. We in the Northeast are in the embrace of the Maple Nation.

I’m thinking about what it would mean to declare citizenship in Maple Nation.1[1]

Salmon Nation. There it was. It’s not the same as “the Pacific Northwest” — a designation that emphasizes the position of this place in connection to others both south and east, namely Washington D.C. and other cities on the eastern seaboard. And it’s not the simplified version of Cascadia that many hold in their mind, which takes a stab at bioregionalism but nonetheless often falls into the habits of using existing state lines as its imagined future boundaries. It deepens the notion of bioregions as gatherings of watersheds; for rivers and watersheds are not merely the water that flow through them, but the many living beings that grow in and feed them as well.

It’s a name that has sparked something for others seeking new ways to restructure governance and identity in this region as well: a quick online search turned up a project called Salmon Nation trying to do just that. Their portrait of the bioregion sees the connection of salmon and ravens not only up into Alaska but down through the rivers of central California:

What’s the point of all this fussing about names? Probably best to be clear here that I think people and places often have many names, with different purposes, different stories, called in by each. I see repositioning oneself in Salmon Nation as a way to open up the possibility that our primary connections to a place might grow beyond human social institutions, and center instead our other-than-human or more-than-human neighbors. It also centers one’s residence in the lifeways of that place’s Indigenous peoples, rather than parcels of land staked out and negotiated by Euro-American settlers.

Of course, I am a white American of European descent, so what does it mean to position myself in this way? One important effect, as far as I can see, is that it actually denaturalizes my presence; I am a guest of the salmon and of those people who have made treaty with the salmon, not some deserving heir of bootstrapping pioneers (be it the 19th century wagon-cart version of pioneering or the late 20th century UHaul version of my parents). But I am also an uninvited guest, which suggests I have responsibilities different from those who have been intentionally asked over. I might offer to wash the dishes more often than not, to make up for the inconvenience, or whatever the equivalent bioregional household task should be. Surely I should learn how my hosts prefer things to be done around here, that I not unintentionally cause offense—a process I expect to take awhile. I attended schools here named for the likes of Marcus Whitman and Joseph Lane, neither of whom were likely to seriously consider the concept of, much less loyalty to, Salmon Nation. Best attempts of progressive educators aside, I know there are some things to unlearn.

“On what basis do we select where to invest our allegiance?” Robin Wall Kimmerer asks later in her essay. “If I were forced, I would choose Maple Nation. If citizenship is a matter of shared beliefs, then I believe in the democracy of species. If citizenship means an oath of loyalty to a leader, then I choose the leader of the trees. If good citizens agree to uphold the laws of the nation, then I choose natural law, the law of reciprocity, of regeneration, of mutual flourishing.”

Robin Wall Kimmerer knows where she belongs, where her home is, and where her allegiance lies. For myself, these are still questions, not fixed answers. My belief is that they will be answered, not by settling myself into some fixed address or acquiring the appropriate governmental IDs, but through seeking and asking, testing and trying. I am here to ask Salmon Nation what it means to be a long-term guest or resident, what its equivalent of citizenship might be; to seek out true reciprocal practices here, to recognize the leadership not of those heading up state houses in Oregon or Washington capitols but the leadership of those remaining in runs in the river. My current hunch is that doing so means you might soon find me trying to figure out how to get rid of some massive pieces of concrete.

Where am I from, and am I home? I might be from here, in the wide valley west of the tall volcano shining with glaciers, and south of the big river that swallows the others as its cuts deep into the rock on its way to the ocean. You can find my house on the flats just beyond a small cinder cone. We have pole beans and peppers growing out front. Am I home yet? Is my tenure as a guest a welcome one? I’ll let you know when the salmon tell me.

That project is likely Gary Nabhan’s work on Renewing Ancient Food Traditions. Here’s one version of the map, though others, including Kimmerer’s own work on Maple Nation, use ones that vary from this: