You owe this piece to Joan Didion. Specifically, to her 2003 book Where I Was From.

The cover image from the original edition—a train’s steam engine breaking through mountain snow, a barely perceptible businessman in a suit receding over the crest of a hill in the background—has been swapped out in later printings for one of the better-known photos of Didion, looking both cool and critical from the driver’s seat of an open convertible with cigarette in hand. Do we credit the designers at Alfred A. Knopf with knowingly enacting the exact shift in hazy, obfuscating myth-building that Didion describes as central to the cultural and economic project of creating the place we now call California, and which she carefully documents in the book in their hands? No, but there you have it—in the choices made by a New York publisher’s marketing department, the passing of one glamorized and half-grasped self-understanding to another that Didion observes in her own family, and in herself: from the stories rooted in the ethos of Manifest Destiny celebrating the ‘self-made’ settlers of the 19th century to the Hollywood and aerospace post-war era that transformed earlier forms of California individualism into consumerist fantasy.

Where I Was From, Didion says, “represents an exploration into my own confusions about the place and the way in which I grew up, confusions as much about America as about California, misapprehensions and misunderstandings so much a part of who I became that I can still to this day confront them only obliquely.” In early chapters she captures the lingering status of the settler ethos in her family’s response to newer, mid-twentieth century arrivals:

“The trouble with these new people," I recall hearing again and again as a child in Sacramento, "is they think it's supposed to be easy." The phrase "these new people" generally signified people who had moved to California after World War Two, but was tacitly extended back to include the migration from the Dust Bowl during the 1930s, and often further. New people, we were given to understand, remained ignorant of our special history, insensible to the hardships endured to make it, blind not only to the dangers the place still presented but to the shared responsibilities its continued habitation demanded. If my grandfather spotted a rattlesnake while driving, he would stop his car and go into the brush after it. To do less, he advised me more than once, was to endanger whoever later entered the brush, and so violate what he called "the code of the West." New people, I was told, did not understand their responsibility to kill rattlesnakes.

But Didion is herself of a new generation, and understands that her grandfather is already interdependent with the changes he denounces. She writes: “New people could be seen, by people like my grandfather, as indifferent to everything that had made California work, but the ambiguity was this: new people were also who were making California rich.”

And, as she goes on to detail, both the old-time Californians and the newly rich ones are both caught up in the same kinds of stories—presenting themselves as self-made yet actually reliant on federal subsidies, be it the riches given away to the railroad companies, the money for water and reclamation projects, or the handing over of land and labor and contracts all to the military and its many private contractors, to corrections companies (who likewise rely on yet more private contractors).

As a critical look both at settler stories and their contemporary forms, and what it means to have grown up shaped by and imbricated in the products made by those stories, I strongly recommend the book. So much so that my local librarians are probably tired of hearing the enthusiastic recommendation I offer up in place of the borrowed volume when they let me know yet again that my copy is very overdue.

But none of this is really the exact reason for this particular essay. The real inspiration that Where I Was From gave to me is a very specific image, one that upended my own visual imaginary of the Golden State. That made it a little less gold, a little more blue.

In an early chapter, Didion takes up the Sacramento River to illustrate that “A good deal about California does not, on its own preferred terms, add up.” The ‘not adding up’ in this instance is “the creation of the entirely artificial environment that is now the Sacramento Valley.” The Sacramento is one of the first examples she offers of that core California mythology at play, with the entire landscape achieved through “extreme reliance of California on federal money, so seemingly at odds with the emphasis on unfettered individualism that constitutes the local core belief.”

Nothing here that’s too surprising, given the passing familiarity we’ve already built here with the history of the Bureau of Reclamation in past posts. But one can know that the natural water systems of California were disrupted and destroyed, and still not have a very good sense of what that might have looked like, how it felt, what it meant for people who lived within the bounds of a different set of natural processes.

That’s what the book gave me, in a short description of one of Didion’s great-great-grandfathers who opts to move to Sacramento, despite how the river was routinely “subject to inundation for several miles back,” how it was “predictably given, during all but the driest of those years before its flow was controlled or rearranged, to turning its valley into a shallow freshwater sea a hundred miles long and as wide as the distance between the coast ranges and the foothills of the Sierra Nevada.”

Let me ask you: is that how you think of central California, of the miles stretching from Sacramento to Stockton to Modesto, along I-5? As a sea?

And how do you think people lived with this inland sea? Didion writes:

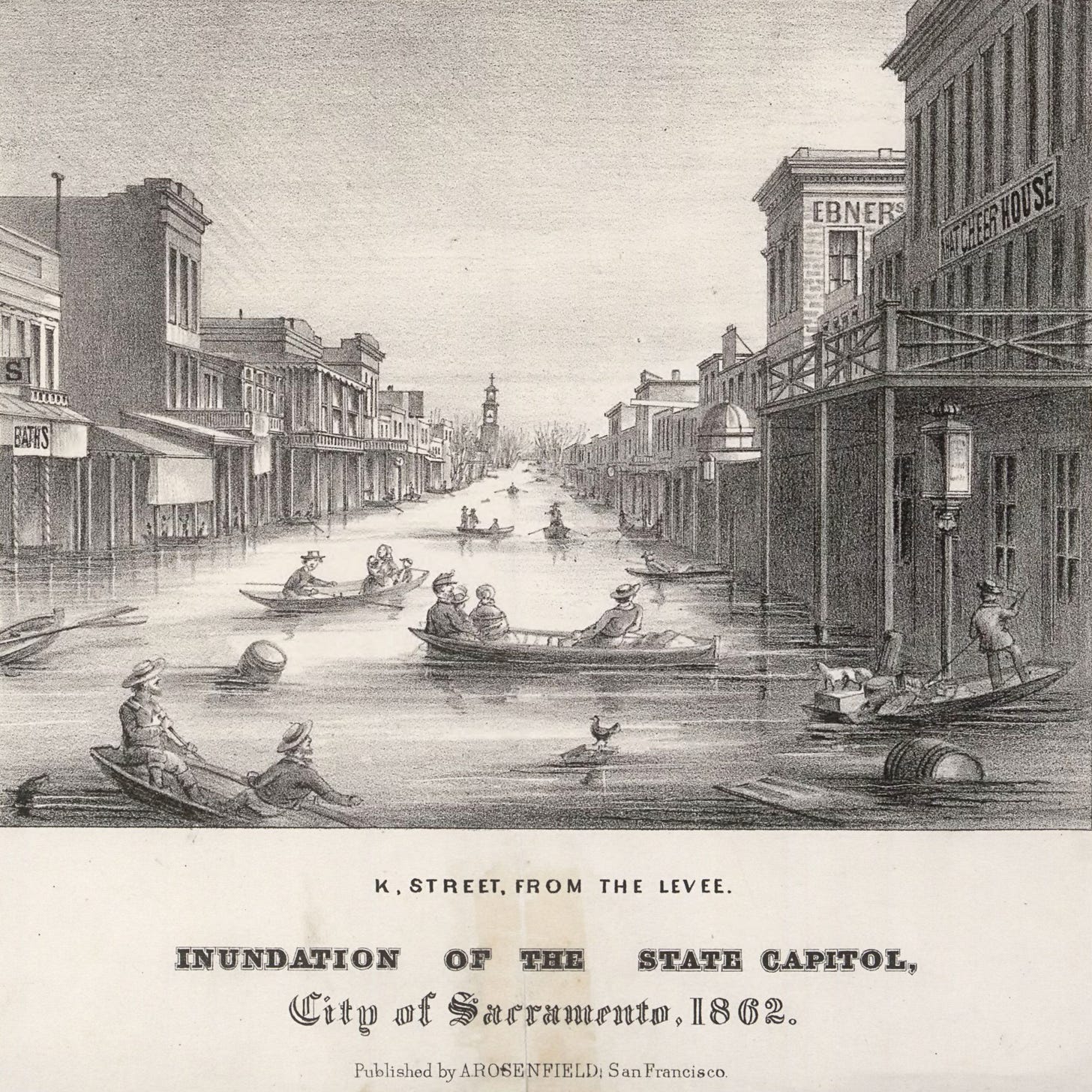

This annual reappearance of a marsh that did not drain to the sea until late spring or summer was referred to locally not as flooding but as "the high water," a seasonal fact of life, no more than an inconvenient but minor cost of the rich bottom land it created, and houses were routinely built with raised floors to accommodate it. Many Sacramento houses during my childhood had on their walls one or another lithograph showing the familiar downtown grid with streets of water, through which citizens could be seen going about their business by raft or rowboat. Some of these lithographs pictured the high water of 1850, after which a three-foot earthen levee between the river and the settlement was built. Others showed the high water of 1852, during which that first levee was washed out. Still others showed the high water of 1853 or 1860 or 1861 or 1862, nothing much changing except the increasing number of structures visible on the grid.

Didion may be too casual here—not all these flooding events were so routine that it was a mere matter of, “Hey honey, I’m taking the boat to work today, rather than the horse—” Some of the more major floods led not only to destroyed homes and lost goods but outbreaks of cholera. The flood of 1862 was especially destructive, wiping out whole communities up and down the West Coast. But it was routine enough that it didn’t get too much in the way; Leland Stanford took a rowboat to his inauguration as governor in early January of that year. (Though he must not have liked rowing all that much—two weeks later, the state capital was temporarily moved to San Francisco.)

But Didion’s casualness provoked me. In our modern imagination, transformative change in a landscape—such as that from a major flood—is primarily something we seek to prevent or control, to will out of existence. When our plans fail, we call it a disaster. Yet what if all disasters weren’t really disasters? What if costly control isn’t our only option? What if, like residents of early Sacramento, we simply took for granted that the lands on which we live are not static entities that we can master once and for all? What if we took radical change as a given, row boats at our side?

What if we took radical change as a given, row boats at our side?

In fact, that could be one way of describing how the Notomusse, Bushumnes, and Pawenan Bands of Nisenan lived along the Sacramento long before miners and merchants invaded the area. While Nisenan also used the river for travel and trade, they didn’t build their homes right alongside the river, but instead on top of elevated knolls, safe from the flooding. Like their Miwok neighbors, they found a way to live amicably with the natural patterns of the river and the broader Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, and had whole lifeways built from the many species well-supported by the delta’s marshes and waterways.1

But attempts to control the river’s flooding cycles meant doing away with much of the delta. Control of the river was closely linked to dispossession and displacement. The money that poured into the Sacramento Valley to help prevent water from doing the same came in part from the 1850 Swampland Act, which provided funds for the reclamation of wetland—that is, its draining and privatization. As the Homestead Act privatized and led to the aridification of the prairies, the Swampland Act did the same to wetlands. The act’s passage intersected with the California Gold Rush, bringing more settlers into the area who took advantage of the new ability to claim land.

Even with the funds and arriving labor power it still took a very long time for anything like reliable ‘control’ of the Sacramento River to be achieved. The city of Sacramento has become less susceptible to flooding, but only after more than a century’s worth of ongoing labor: dams, levees, diversions, and more. The work continues, to some extent, even today. That’s 170-some years of trying to protect a settlement pattern born from a willfulness to deny both common sense and reality.

Some might say that what’s done has been done, and that while it’s a fun historical exercise to remember that California’s Central Valley once looked like a sea and that life could be lived in a way tolerant of the river’s self-generated movements, that time is too far gone and we’re too entrenched in the current scheme of development to do anything different. Others know: what we’ve built to avoid certain risks have only elevated others—or sunk them, as much of the land in the delta has been. This sinking, or subsidence, along with increasing salt water levels and other issues, all complicate the status quo, and could possibly cause the very flooding all those years of labor have attempted to prevent. For an idea of what I’m talking about, see the story “Want to Prevent California’s Katrina? Grow a Marsh” in Bay Nature magazine, which also digs into a key reason to restore, rather than forget, California’s wetlands: they’re massive systems for storing and cycling nutrients of all kinds, including carbon.

The piece reminds us that wetland ecosystems, while only 5 to 8 percent of the planet’s land surface, “contain between 20 and 30 percent of the world’s soil carbon.” Researchers think that the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta “may have once held the largest freshwater wetland carbon reserves on the West Coast,” but that, since the era of reclamation in which much of the delta was drained, “it has released an amount of carbon equal to one-quarter of California’s forests.”

From that perspective, wetland restoration is a little less trivial. And of course, de-channelizing rivers and restoring waterways also makes it possible to continue and revive many Indigenous cultural traditions. But we might say it allows us to continue any traditions at all, save for those that keep us trapped in thinking of land and space and the rivers that traverse them as strictly bordered and static, rather than entities that are ever-changing and always moving.

I said you owe this post to Joan Didion, which is true. But Didion’s book, as much as it successfully examines the ‘confusions’ in which she grew up, still doesn’t nearly get to their roots, or help us fully unravel the continuing confusion about the nature of the places in which we live, be they in California or elsewhere.

It’s not just the aggrandizing stories of the self-made 19th-century pioneer or 20th-century businessman that need to be pulled apart, but the myths about the land itself on which they live—what it has been, and is, and will be. Just like the social divisions between old and new settlers may not hold up under scrutiny, so may some of the classic distinctions we’re used to drawing—even something so basic as where the sea ends and dry land begins.

Thanks for reading Unsettling.

Until next time,

Meg

See “Native Spaces: Sacramento” in We Are the Land: A History of Native California.