What Ball Gowns Have to do With Land Return

A look at museums and the movement for cultural repatriation

“Tax the Rich” down the back of a dress; David Wojnarowicz art turned into raiment; traditional tattoos worn by models who also happen to be land rights activists1—the Met gala made headlines a few weeks ago in a way it hasn’t for some time, in part because of some of these particular outfits. Generally the aim here at Unsettling is to avoid getting caught up in the false prioritization of the internet news cycle. Does the Met Gala already feel like very old news to you, and completely trivial to discuss given that the moment has passed? Probably, which helps show why it’s good not to become too attached to the news as a guide for action.

Yet I found the momentary focus on the Met potentially useful, and wondered if we’d see deeper discussion about what that museum represents, when it comes to challenging the status quo of economics and culture. Alas, we were mostly treated to more takedowns of AOC’s performativity. (At an event where everyone was performing, no less—isn’t performativity the point of a costume gala?) I saw a whole lot more of that and a whole lot less reference to critiques of the museum’s inability to adequately address issues of exclusion in its collection or its failure to remedy concerns from workers at the Met and elsewhere about internal racist dynamics. (Those concerns are ongoing, even as counter-critiques of the museum ‘going too far’ are already in circulation.)

And what one definitely did not see—though I think a dress flaunting a call for redistribution certainly paved the way for such conversation—were calls for repatriation of cultural objects and a discussion of the outright theft or other questionable methods of acquisition enabled by colonialism that allow a museum like the Met to exist in the first place.

When I moved to New York for a short spell in late 2013, I was tremendously enthusiastic about the ability to visit all these "world class" museums which I had read about but never seen. I did not yet equate “world class" with "world theft," though now I would consider the first to imply the second. Yet it was by attending exhibits at the Met that I began to learn, once again, about the ways elite institutions participate in keeping the history of colonialism at arm’s length.

I’ve been through this process multiple times already in my life, with churches, universities, and workplaces, all organizations in which I have at first found community and then later come to see how they hid or casually glossed over violent pasts, or remained complicit in upholding racist policies or cultural norms. (Or sexist policies and cultural norms. Or norms reinforcing class discrimination. It’s always something; take your pick.) 2020 became the year that many went through this process for the first time, forced to look at what they had previously willingly ignored.

For those of us who have been involved with or benefited from major institutions, that moment of realization that, yes, this one too, is also complicit, can be hard. The Metropolitan Museum of Art is one of those institutions that seems to elicit warm feelings among many. Its openness to the public—paying for admission is optional—can help engender that, as can the experience of attending the museum itself. Its vastness allows for a certain kind of meditative state to take over as one contemplates the sheer creative power of humanity. Yet just like so many of our institutions, the goods have come at a cost.

It can be tiring, this constant peeling back of the curtain to expose the problematic power games behind the major social establishments. There’s a time when one wants to just sit back and enjoy something, yes? I can hear some of my New York friends thinking that now, not really wanting to read on. Doesn’t one go to the Met to get away from this? To quit thinking about all the hard problems out there on the street and just stand quietly next to a friend and take in some tremendously skilled piece of art or craftsmanship?

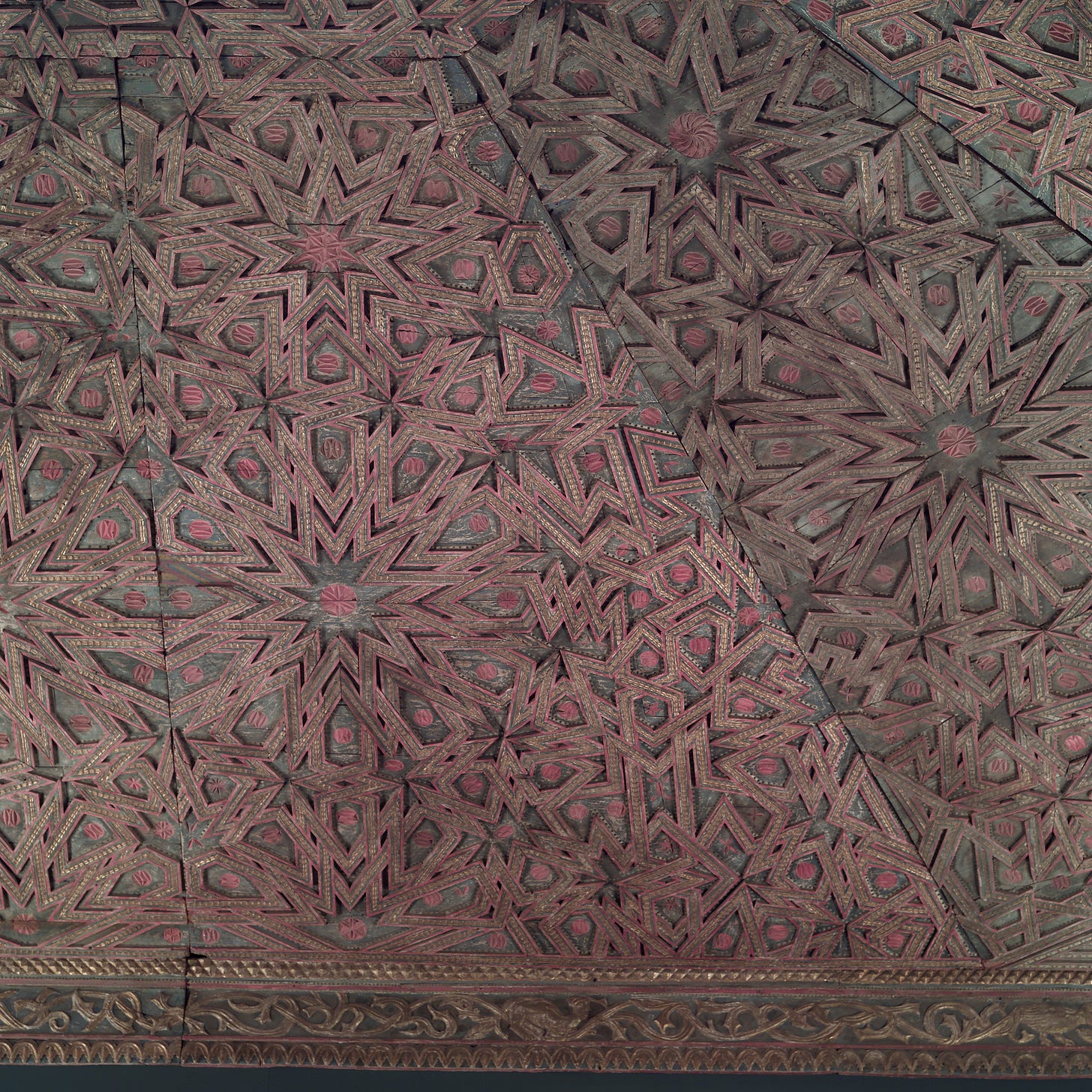

Certainly that’s how I often approached the Met—as a respite, or escape. I have some favorite spots: a bench in the East Asia wing, in front of certain ceramics and scrolls, that I found to be quiet and calm more often than not. I like to stand and stare straight up at the intricate Islamic stars of a 16th century ceiling, or out certain windows that in the afternoon catch the light and the flutter of leaves in the park outside.

But then there was the night I went to the exhibit on Plains Indian art. That exhibit, The Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky, garnered a large amount of positive press, in outlets like The New York Times. And while the museum did make some efforts to change past practices—they brought in Native consultants, and made sure to include contemporary artists rather than treating indigenous art traditions as simply a thing of the past—it was also the first time I saw, in a contemporary context (as opposed to in some decades-old textbook or on a deteriorating sign along a state highway) the phrase “manifest destiny” used completely uncritically. As in, “then the United States fulfilled its Manifest Destiny,” written in big type on one of the curatorial panels describing changing forms of life and art during the 19th century. There it was, authored by some New England professor of history, who offered no additional contextualization. No explanation of manifest destiny as an ideology used to justify land theft, or as a ploy by politicians to gain or maintain power. Only manifest destiny as some kind of strange… fact?

That almost aggressive lack of honest historical perspective kept me attentive to the other forms of erasure active in the exhibit. Again and again, there would be notes about how knowledge of the artist “had been lost.” This grammatical sleight of hand avoids responsibility for that act of losing. While there were some much older pieces in the collection, most weren't from thousands of years ago. Many were within the last century, only a few generations past. There is little reason we—and I’m using the very broad, dominant society “we” here—do not know the origins of such pieces other than we sought to destroy their very creators, and didn’t even bother to capture their names in the process.

While I did not see them at the time, there were critiques made of the exhibit that focused on this lack of contextualization, and the absence of genuine collaboration with Native American curators. In the room, it was clear: even an exhibit intended to center indigenous artists could continue to marginalize, by failing to honestly address the dispossession and genocide that sit at the heart of American history, which includes its art history.

This same evasion and erasure is present not just in this exhibit, but in the average description of most art pieces in most museums. Look for such phrases as “this sculpture has been acquired…” Passive voice all the way through, with vague word choice—“acquire” could mean so many things—to boot. Certainly one will never learn the price paid for such an object, the chain of transmission, or who died so that the Met could offer it up for mass consumption.

Yet, as they have since they were first taken, people are pressing for greater transparency and true accounting of museum acquisitions, and in many cases, demanding return of objects. This is not only in the U.S.; repatriation of cultural items is a global matter, just as colonization was a global matter.

The Met, for instance, just this summer returned works of Nigerian art that went missing from a museum in Lagos in the early 1950s and found their way into a private collection and then a number of museums, including the British Museum and others in Europe.

And objects have come back to Turtle Island from other continents. In July, the Weltkulturen Museum in Germany repatriated a shirt to the Teton Lakota. Again, we are not so many generations away from these original acts of dispossession; the shirt was returned to the great-grandson of its original owner.

A few years back the Met also returned statues to Cambodia, after Cambodian officials provided evidence that the statues had been stolen. The Verge used this return as an opportunity to look at the broader issue of repatriation, including the inadequacy of standards and processes set by the United Nations. As they note, the “UN committee established following the [1970] convention has presided over just six cases of successful restitutions in the past 40 years.”

That inadequacy might explain why Mwazulu Diyabanza, a French resident born in the Democratic Republic of Congo, has been causing a stir this last year by staging dramatic actions in which he attempts to remove African objects from various European museums, including the Louvre and the Quai Branly. Says Diyabanza:

The House of Culture was destroyed… The soul of the real Africa was stolen, so we have to repair this. And to rebuild, we'll start with bricks, the ones that were stolen, and those bricks are those very objects here — they're the remnants of our ancestors that are buried here.

Diyabanza’s actions, which he refers to as “active diplomacy,” have helped accelerate conversations about repatriation in Europe.

And while one could take Diyabanza’s description of “those very objects here” as “the remnants of our ancestors” to be figurative, the truth is that the issue of repatriation is also, often, literally about physical remains. It is not just art and cultural objects that museums and other academic institutions hold; it is bodies.

Arguably slightly more effective than the UN convention is the 1990 Native American Graves and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in the U.S., which requires institutions receiving federal funding to return not only sacred and funerary objects but ancestors. Under Deb Haaland, the Department of the Interior is currently investigating the extent of bodies that might still be held by former U.S. boarding schools, a move made after recent events in Canada highlighted the hundreds of children who died at residential schools there. Once again, we’re not talking about the bodies of those lost many years ago; we’re talking about the very recent past—about the classmates of people still alive. This year, Canada promoted the National Day of Truth and Reconciliation (also known as Orange Shirt Day) from an ‘observance’ to an official holiday, as news of graves and then more graves of young bodies at residential schools were found.

In the U.S., despite NAGPRA, repatriation of bodies at some boarding schools continues to be a challenge. Schools like the one in Carlisle, PA, were run by the Army, which has been allowed to maintain its own process for repatriation with a more elaborate set of red tape for families and tribes to work through. We’ll see if Interior’s investigation helps alter that allowance to make the repatriation process more tenable.

Boarding school graves may seem to be a different matter than museums and their collections of art and objects, but museums have also collected human remains. This year also brought the news that the Penn Museum not only held but used in classroom instruction remains of children who died in the police bombing of the MOVE complex in Philadelphia.2 From Artforum:

THIS APRIL, the University of Pennsylvania admitted to the public that human remains from the charred rubble of the devastating May 13, 1985, police bombing of the MOVE complex in West Philadelphia had been given to Alan Mann, an anthropologist on the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania from 1969 to 2001. He was asked to provide forensic analysis of the bones; they are now believed to belong to either or both Tree and Delisha Africa, thirteen and twelve years old, respectively, at the time of their death. Mann took the bones with him when he moved to Princeton University, but they were subsequently returned to the Penn Museum, where they have been kept for the past half decade—all this time, the girls’ mother believed their remains had been interred. In a forensic-anthropology course taught by professor Janet Monge, pieces of pelvic and femur bones were used as a “case study,” with the instructor offering graphic descriptions of their diminutive size, the damage they sustained, and their smell: “Like an older-style grease,” she said. Another set of remains belonging to the bombing’s victims was ordered for cremation and disposal of by Philadelphia Health Commissioner Thomas Farley in 2017, but was found in a box in the basement of the city medical examiner’s office in mid-May.

If you want some art school analysis about the ways in which museums uphold imperialism through their collecting efforts, including their collection of human remains, read the whole piece.

I didn’t know much about cultural repatriation issues before I began researching this post. But I did know that the way white supporters of land return, like myself, talk about land repatriation often feels like it is missing something. In some ways, the way we discuss land return can reenact that colonial moment that divorces land and culture from their mutual sustenance. It has never only been land that was taken; it has been entire life ways and livelihoods, whole languages, whole forms of relationship.

The mission of the encyclopedic museum, as well as much of the scientific enterprise in which it is embedded, is to pull things apart, to sever the relationships of the items under study and set them in an order deemed more objective, to look at them from some ostensibly universal viewpoint intended to provide a more singular ‘correct’ meaning.3 Curiously enough, this viewpoint tends to be built in geographically specific places—the major metropolitan areas of European and American cities that serve as the hubs for capital and for the gathering of the exploits of the many extractive industries. (Consider that J.P. Morgan himself was president of the Met for a time.)

Repatriation alters the relationship between margin and center, between that colonial metropole and the territories exploited for its sake. It says that objects and cultural production are not isolatable molecules that can be plucked from context; their meaning does not come only from objective analysis. It denies the impulse to achieve understanding of a thing by pulling it out of place, by cutting away its relationships. It asserts, to the contrary, that art has a home: that it belongs, that relationship matters, and that neither its plundering nor its use for profit can definitively erase that first belonging.

Curators create meaning through juxtaposition, through providing new relationships, new contexts by which a work or set of works might be understood. I am not opposed to this kind of meaning-making. But the institutional framework of encyclopedic museums like the Met embeds curation within not only a less-than-transparent network of detachment and commodification but also within a space that, despite endless placards with quotes from diverse sources, mostly serves to hide the original context of a work and the chains of transmission leading to that museum’s ownership. It is only the last transaction that ever matter: “Gifted from the estate of…” That thieving might have enabled the giving receives no mention. Nor does the potential for other meanings or other experiences with this object, should it be restored to the place and web of relationships that first brought it to life.

Repatriation honors that web of relationships, and reaffirms the bond between culture—ways of life—and the land that informs it. As we talk about “living on stolen land,” we can remember that much else was also stolen to enable the taking of land. This point may seem obvious to the extreme, but as with most things, the details matter. How colonialism serves as the foundation for nearly all our modern institutions matter. One way it plays out in cultural institutions is by reinforcing a conception of culture as separate from the physical places in which it is born. As we support land return, we can try to challenge this separation, and understand that the goal is not return of some isolated parcel of real estate, but restoration of a relationship that includes people, place, and all they produced together.

The Met Gala is a silly event. But it’s also a yearly opportunity to discuss all of the above. Will we be given the same obvious chances to widen the conversation that we were this year, the next time around? Who knows—I’d guess some of that depends on whether the fake media controversies and extended coverage hindered or helped this year’s fundraising effort. Whether it takes a little more effort or not, it remains a time to help highlight all the wealth that museums have taken in, and whether or not they’ll step up to the challenge of restoring that wealth to those who helped generate it in the first place.

If you’d like to continue to learn about repatriation, you can find good resources from the Association of American Indian Affairs and their International Repatriation Project.

If you would like to learn about the importance of Quannah Chasinghorse’s tattoos, she explains their meaning and context in this Instagram post. Apologies for not including an image of her awesome outfit; Instagram went down while I was working on this. [UPDATE: We’ve since been able to include an image.]

If you are unfamiliar with the MOVE bombing, take a moment to learn about the time that a U.S. police force bombed inhabited city blocks, destroying some 60 buildings. Here’s one piece from the 30th anniversary: https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2015/05/13/406243272/im-from-philly-30-years-later-im-still-trying-to-make-sense-of-the-move-bombing

Yes, there is plenty of critique of this form of scientism within the natural and social sciences both, nowadays. But at the time museums like the Met got their start in the 19th century? A little less so.