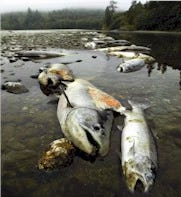

“After the fish kill happened, dam removal became the only option for Yurok because we could not allow for our river to be that sick ever again. We just couldn’t.” — Amy Bowers Cordalis, Yurok Tribal member and Principal, Ridges to Riffles

The last time I visited the Klamath River, in early fall of 2020, I came with dreams of swimming. I knew it was unlikely, but couldn’t help myself from fantasizing nonetheless. It was still a river, after all. My fantasies were dashed the moment we neared the water, thick with swampy green algal blooms. Smell of muck and rot rose in the late September heat. We fell to our backup plan and stayed on land, rode our bikes along the river instead.

I had known the river was unwell; had met people who were part of the broad network pushing their collective shoulders against the creaking bureaucracy governing the dams on the river, as though the halls of state and federal offices were the dams themselves they were trying to bust through. Still, I hadn’t quite understood the urgency of their work. That single afternoon along the Klamath—the sheer obviousness of its illness to my own senses—grafted onto what little I knew then about dams, and made me a more active advocate for their removal. The precariousness of the moment probably helped. The future of the Klamath was still hanging in limbo; one of those times where it feels like one ought to jump on board because just a few more folks might somehow tip the scales.

For despite the growing consensus in favor of removing all of the Klamath’s lower four dams, only a few short years ago, their fate was still in question. The timeline for removal had already proved longer than many had hoped. And just then, the agreement signed in 2016 that set the foundation for the removal process seemed newly shaky: FERC (the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission) was supposed to approve transfer of the license for the dams from PacifiCorp, who had been running the dams, to the Klamath River Renewal Corporation (KRRC), a non-profit collaboration including tribal governments and the states of Oregon and California. But in July of 2020 FERC didn’t allow PacifiCorp to completely step out, causing many to wonder if all the carefully negotiated plans were about to fall apart.

We’re further along in the story now, and we know how it’s turning out: the first dam removed last fall, and reservoir drawdown for the others, needed for their dismantling, is underway. We’re at the moment where this result can begin to feel inevitable, like something that would have always happened. Now you can open up any West Coast newspaper and read articles on how the dams had ceased to be economically viable, and their removal a necessary strategy to restore the river’s health. (Here’s some sample video coverage from Seattle, and an excellent piece from last weekend’s L.A. Times.)

So now is also a good time to remember how this has not always been the state of affairs. To remember back to 2002, when PacifiCorp was pursuing relicensing of the dams just as they were—dams that had not even the most basic of amenities to aid in fish passage, such as fish ladders. How in that year, a contentious order from the George W. Bush administration diverted water from the Klamath for agriculture. The result: thousands upon thousands of dead salmon on the river’s shoreline.

It’s that moment which reignited calls for taking down the dams. It began with the kinds of actions whose effectiveness many people are often skeptical about: rallies, community teach-ins, sign-waving protests. Showing up at shareholder meetings with requests or heckling. Calling out corporations in the media. But those actions escalated, to successful tribal suits on behalf of the salmon, requiring retrofitting of the dams should they be relicensed. PacifiCorp ran their numbers and they no longer added up. Suddenly, dam removal seemed to have real traction, and the table of conversation partners was large and active. And today? Today one dam is already down, the others soon to follow.

I’ve been spending altogether too much time trying to absorb all the media currently being generated about the Klamath dam removals. You can practically make a full-time job out of it, there’s that much. I think what draws me in is not merely the stunning photography of a major engineering project going down, or all the headlines of “the world’s largest dam removal.” It’s also this potentially quick-fading history of the social organization that made such a thing possible. The dams going down on the Klamath is a true story of people showing up again and again in the face of callous energy execs and forever changing local and federal administrations, showing up through and despite their own shifting and often strenuous personal circumstances. And not just for a year or two; for decades.

For the truth is that the story is much older than the “Un-dam the Klamath” movement reinvigorated after the 2002 fish kills. While the story of the decimation of salmon runs by dams throughout Salmon Nation is sometimes told as one of slow and moderate impact, the effects on the salmon populations by the dams forced on the Klamath were so immediate that California outlawed commercial fishing on the river in the early 1930s (the first dam went up in 1906). The ban included any fishing by the Yurok, who relied upon it both culturally and economically.

The Yurok, at that time without a tribal government, their land broken apart through allotment policies, continued to fish anyway. This insistence on their right to fish led to a parallel chapter of the Fish Wars that we discussed recently (“Fishing in Solidarity,” in January). A first major win came in 1973, in a case called Mattz vs. Arnett. The State of California argued that the Yurok’s right to fish on the Klamath didn’t exist because this was not Indian territory; the Supreme Court disagreed. With the Boldt Decision out of Washington State only a year later, it should have made smooth sailing (or smooth boating, rather).

Only officials in California remained stubbornly and violently persistent, finding new routes to prohibit Yurok fishing. Stories abound of armed and armored officers on the river ramming Yurok boats and attacking those who tried to assert their fishing rights. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife closed down all fishing on the river in 1978. Court cases continued throughout the 1980s. To some extent, the matter on the Klamath still isn’t finished; drought conditions lead to new decisions each year about how much water to allot to fish or agriculture, and each year the regulatory and legal landscape is different.

In trying to piece together this specific history of the Fish Wars, I’ve been finding that many of the more accessible accounts of the struggle for Yurok fishing rights taper off around that 1978 date. They don’t really explain what happens with the contrasting state action and legal rulings, and instead pick up again in 2002 and Un-dam the Klamath efforts. This is a curious elision, one that doesn’t put us in a good place to understand what has allowed the tribe to become the force it is on the dam removal front (and many other fronts; news came just this week of the groundbreaking co-management agreement between the Yurok, California State Parks, and the National Park Service, as the Yurok receives back part of its ancestral territory in the redwoods).

But if you dig around in all that media I mentioned, you can begin to piece together traces of other stories. I’m not a tribal member or tribal historian, so my knowledge is limited here. But one thread during those years between 1978 and 2002 that I feel I’ve encountered repeatedly has to do with the raising of young people to know and take pride in their culture, and to take on leadership later down the line.

This is the kind of history that also gets easily lost; we tend to tell our stories with our heroes pre-formed, with some intrinsic set of qualities that allows them to step up and take decisive action at just the right moment. We don’t usually talk about decades of aunties and grandmothers pushing young kids out of their house to go attend the protest for the salmon. But youth leader Sammy Gensaw of the Yurok does, when describing his own dedication to the Un-dam the Klamath movement. And the legal skill helping move all those rusting bureaucratic pylons out of the way so the dams can come down? That comes from someone born in the immediate aftermath of the Fish Wars, who was raised steeped in their history and in the culture of fishing. That person is Amy Bowers Cordalis. Profiled by High Country News back in 2018, her story is also newly captured by Swiftwater Films (the outfit behind some of the best photos you’ve seen of the dams coming down). If you want both exciting video of the dams coming down, and the backstory of how it all came to be, you’ll want to watch it:

This really is a historical moment, which means that all the press about the dam removal project might really be the “first rough draft of history,” as the expression goes. It seems important then that we capture as much of the longer backstory in that first draft as we can, so that if textbooks are written years later, they aren’t reduced to absurd accounts of multinational corporate benevolence or the leadership of a few government officials. And to a large extent, much of what is out there is doing a better job than has often been done, making sure to capture the fact that this moment is truly the work of many hands and many nations (there are multiple nations in addition to the Yurok along the Klamath and its tributaries). The scale of collaboration has been enormous.

I think that’s why I keep reading one article after another, to etch that fact in my mind: in this moment when we talk so much about how impossible it is to get anything done these days, politically, something like this can still happen. Years of individual and collective effort turn into genuine material change. Dams can go down, and hundreds of hands will help billions of seeds and starts go into the ground, and the life of a river can come rushing back.

It’s not such a long drive from where I now live back to the same spot on the Klamath where I stopped briefly in 2020, unable to wade or swim. Maybe one day this summer I’ll quit watching dam removal videos and go see for myself what has already changed. Maybe I’ll even be able to step in, and feel the coolness of the river wash over my feet. I know if I can, there’s a long list of people to thank for it, from community organizers to ecologists to the folks who know how to do this:

Thanks for reading Unsettling. If you’ve missed our prior coverage on rivers and dams, see some of the links below. We’ll be back soon with an update on some of the other major dam removals under discussion, including the Lower Snake dams.

Until next time,

Meg