Rivers and Dams, Resource Roundup: Part 1

Podcasts! Videos! Snarky articles! We've got your learning style covered.

Thanks to those of you who have let me know that you appreciated or were intrigued by the recent pieces on rivers and dams. (If you missed them, check out “This River is Super” and “For the Greater Common Good?”) To follow up, I’ve pulled together some resources that delve into the history of how we use certain rivers, as well as dams and water policy, and the many consequences (both good and bad) that have resulted for communities.

Today: Learn about the watershed for the continent’s biggest city; see a video showing how a hydropower dam closed off common fishing areas for many Northwest tribes; and get more familiar with some of the thorny issues surrounding the use of water on the Colorado River.

Next time: Discover major dam removal projects in the works, and dive into the active movement to normalize such decommissioning.

Podcast Recommendation: Views from the Watershed

Turns out, one could be intimate with a watershed. With watersheds within watersheds.

From “Questions From and For the Road” (Unsettling, February 2022)

A few weeks ago I wrote about one of my first encounters with someone seriously engaging with the land around them, including their knowledge of local watersheds, and just how eye-opening that was for me as a young person. These days I’m more familiar with the bioregional dictum “know your watershed.” Yet most of us live in places where the watershed has been, intentionally or unintentionally, invisibilized. One of the most basic ways to know about a place, or about a being like a river—to go and take a look at it—gets a lot harder when it’s shunted into underground tunnels or kept in reservoirs hidden behind fences with “no trespassing” signs.

So I was really happy to learn about a new project, Views from the Watershed, a podcast that helps bring to life the presence and history of some critical watersheds in the Catskills, which house not only the water supply for New York City but also the Delaware River Basin, which provides water to New York, New Jersey, Delaware, and Pennsylvania.

The podcast is put together by artist, educator and counter-cartographer Lize Mogel, whom I happen to know through work we did together on participatory budgeting, not so long before she began hosting workshops as part of Walking the Watershed. With Views from the Watershed, you can have Lize as your tour guide, even while driving or walking the watershed on your own, or for that matter, while just scrolling the internet from your couch.

The creation and protection of the watershed was, obviously, instrumental for building New York City as we know it today. Yet, like many diversion projects, it involved displacement and altered the relationship to the land and water of those living within the watershed. “I wanted to honor the history of the displacement caused by infrastructure construction and its ripple effect through generations; and to focus on the transformation of that very inequitable relationship into a more mutually beneficial one,” Lize told me. This history unfolds throughout 15 podcast episodes (best listened to in order), as you hear stories from the viewpoint of the many different people who have connections to the Catskills. You also get a sense of how collaborative policy making and community organizing can help repair some historical harms in Episode #9, “A Seat at the Table.”

For all you New Yorkers on this list: print a map the next time you go hiking or visiting in the Catskills and learn a little about your water supply along the way.

Views from the Watershed is available on Apple Podcasts, Anchor, Spotify, Overcast, Stitcher, Google Podcasts, Pocket Casts, Castbox, or Breaker.

Video: The Drowning of Celilo Falls

Oregon Public Broadcasting just re-released a segment originally produced in 2008 that tells the story of the loss of Celilo Falls, submerged in 1957 by the building of the Dalles Dam, which was put in place for hydropower. The dam broke the 1855 treaty that guaranteed access to fishing at customary locations. March 10th marked the 65th anniversary of the drowning of the falls, possibly the most important fishing site for many tribes in multiple states up and down the Columbia River.

See footage of traditional salmon fishing at the falls before they were inundated, and learn about the 50-year struggle at Celilo Village to receive the housing promised by the Army Corps of Engineers when the dam first went in.

Honestly, the film glosses over many of the details of that fight. As parks for windsurfing and other forms of recreation were funded and built in the decades following the damming of the Columbia, time and again, funding and construction were delayed both for fishing sites and homes to replace what was lost at Celilo. Those who want to learn the details and hear about the efforts led by Chief Tommy Thompson and others will find the book Empty Nets: Indians, Dams, and the Columbia River a useful supplement.

Still, the segment is a quick introduction to the topic, and illustrates yet again that displacement and the loss of the commons by dams is a current and live issue. And it sets to rest a concern many had about Celilo Falls in particular: that the Army Corps of Engineers had not merely submerged Celilo, but blown it up. Thankfully, imaging technology has helped to alay such fears, though this knowledge, too, took decades to produce.

Longer (Snarkier) Read: “Dead Pools: The dehydration of Arizona”

Dams effectively bogart a river. There’s more than one way to do that to a water source, though, and Arizona is a state soon to experience the full consequences of a century’s worth of bogarting, both by itself and others.

When it comes to groundwater, for instance, the usual tactic to capturing more than one’s share of the water supply is to build deeper and bigger wells, with more powerful pumps, than your neighbor just down the road. In an article for The Baffler last November, Zachariah Webb details how agricultural overdraw of groundwater has compounded the already troubling water situation in Arizona. The state has been overdrafting its aquifers since the 1950s. Webb cites the conclusion of Arizona-based water policy expert Robert Glennon when noting that such excessive pumping of groundwater has “dried up or degraded 90 percent of the state’s once perennial streams, rivers, and riparian habitats.”

The state has attempted, belatedly, to address such overdraw—largely carried out by large corporate farms—through the creation of “active management areas,” or AMAs. While riddled with legal loopholes, AMAs do help limit certain kinds of water usage, but they don’t yet cover many areas where obvious overdrafting of water is happening. Organizers in southeastern Arizona, for instance, are actively petitioning to add AMAs to the Sulphur Springs Valley, where local residents have seen their well levels drop or go dry as large farms come in to take advantage of the lax regulatory environment.

While alfalfa farmers in rural areas are busy tapping out their neighbors’ drinking water, the rest of the state is busy ignoring the fact that, legally, they are last in line when it comes to water from the Colorado River, even as they finally have the means to distribute that water for irrigation and other uses.

Webb does a good job of summarizing the long and drawn-ought dispute over the Colorado Compact and the building of one of the more questionable pieces of infrastructure put in place by the Bureau of Reclamation, the Central Arizona Project (CAP). For those intrigued by the material I pulled from Marc Reisner’s Cadillac Desert back in February, but looking for a bit of a Cliff Notes version complete with updates on the current fallout of the Bureau’s work, Webb’s piece gets the job done. Here’s his takeaway on CAP:

In 1993, the Bureau of Reclamation declared CAP “substantially complete” and exceedingly over budget: originally estimated to cost some $833 million, it came in at $4.4 billion, earning it the distinction of being the largest and most expensive water transfer project ever completed in the United States. It was also the stupidest. The same year, Arizona’s governor convened an advisory committee that promptly concluded the project to be fucked: agricultural and irrigation districts would struggle to pay for the necessary diversion systems from the mainline aqueduct, and it would be “reasonable to assume that at some point most or all of the irrigation districts may choose or feel compelled to seek the protection of federal bankruptcy court.”

The only way that Arizona managed to receive funding for the Central Arizona Project in the first place, though, was to finally acquiesce to California’s demands to be first in line for water from the Colorado:

But to secure the necessary support from California, the act included a provision that would prove to be both CAP’s and Arizona’s undoing: in the event of drought, California would receive its full entitlement to the Colorado River before Arizona would receive a drop.

And drought has finally come, with the Bureau of Reclamation officially declaring shortages in the Colorado River Basin in August of 2021, and expecting to require more extensive cuts to water usage in only a few years, as the river’s flow (which was already overestimated in the compact) is forecasted to decrease.

How will Arizona respond? As Webb bluntly states: “There is no real plan in place to deal with any of this.”

Aha. Well, if you want your bad news with a solid dose of sarcasm, The Baffler has it for you.

Shorter (And Prettier) Reads: High Country News on Indigenous Water Rights and the Colorado River

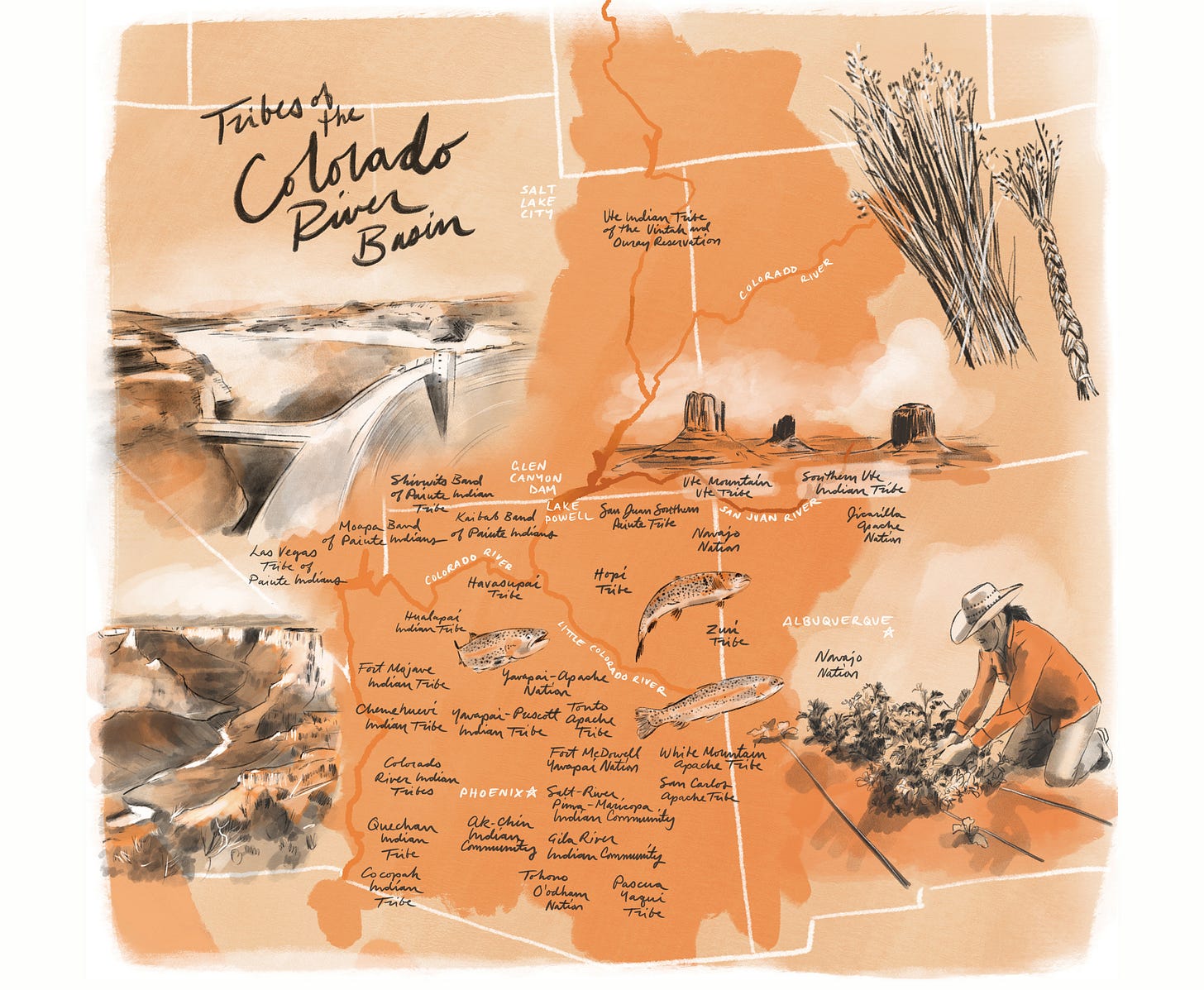

Push may come to shove, however, at long last, as the overdue renegotiation of the Colorado River Compact will take place over the next several years. High Country News, in its March issue, features three shorter, connected pieces on the collaborative efforts of the Colorado River Indian Tribes as they seek to make sure they are fully involved in the decisions about future water usage in the southwest. The series is tied together by the warm rust and charcoal watercolors of artist Gabriella Trujillo:

The backstory, as usual, is one of failed promises:

U.S. water policy, like the reservation system, was crafted to eradicate Indigenous ways of life and people. As reservations confined tribes to one location, forcing them to transition to agrarian lifestyles, the federal government, as their trustee, failed to build or provide funds for up-to-date water infrastructure, allowing the U.S. to effectively control Indigenous water access. In 1867, two years after CRIT’s [Colorado River Indian Tribe’s] modern reservation was established, the Bureau of Indian Affairs authorized $50,000 for building the Colorado River Indian Irrigation Project. The project was ultimately never finished, a recurrent theme when it comes to Indigenous water infrastructure.

“We don’t have the full rights to our water,” Flores said. “That’s the bottom line.”

However, this time, there’s also a bit of a twist and the potential for change, given some interesting case law:

But by establishing tribes as the senior-most water right users in the basin, the U.S. tied itself into a legal knot. The Winters doctrine, which became law in 1908, confirmed the seniority of Indigenous water rights. Winters v. United States was a Supreme Court case that focused on Montana settlers who built a dam on the Milk River, which interfered with agriculture on the Fort Belknap Reservation. It established that the reservation’s creation reserved water rights, and that those rights were exempt from appropriation under state law. In effect, it meant that tribes were not subject to the “use or lose it” policy that defined state water law.

Through new coalitions and partnerships, tribes along the Colorado River are looking to put this legal precedent to the test, and make sure that both their interests (and that of the river itself) are represented as the flawed Colorado River Compact at last gets an update in 2025. What has it taken for them to be at the table, and what might the future of Indigenous water rights to the Colorado look like? Read the full series to learn more and see more of Trujillo’s artwork:

“Colorado River, stolen by law” (Pauly Denetclaw)

“Tribes along the Colorado River navigate a stacked settlement process to claim their water rights” (Pauly Denetclaw)

“Tribes negotiate for a fairer future along the Colorado River” (an interview with Daryl Vigil by Christine Trudeau)

That’s it for this first installment of recommendations. Have any of your own? Please share in the comments!

Happy Spring Equinox,

Meg