You know the experience of meeting someone multiple times and still forgetting their name? You’ve met but you don’t really know them, and to be honest, you’re maybe not really trying. Then maybe through other friends you learn that it turns out they’re quite the person about town, someone you really should know, someone who could open a lot of doors into spaces that matter to you. Now it’s become a little awkward because you’ve blown your first impressions and those initial moments for organic connection, and you’re trying to get re-introduced without seeming weird about it, because clearly you were a little indifferent on the first go-around, unintentional though it may have been.

If you’re not susceptible to such patterns, I’m glad. I’ve learned that I can be, usually without meaning to — it’s just a result of meeting so many people all the time. But here’s something new: I’ve also learned it’s possible to have that same kind of dynamic with a plant.

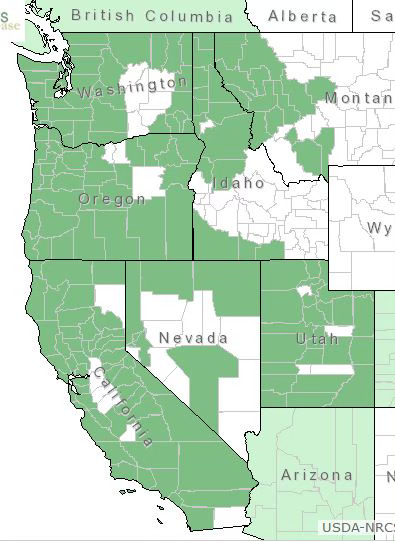

Turns out I’ve seen Holodiscus discolor all over the place — up and down the whole West Coast, probably. And I’ve really been giving them the cold shoulder.

At a quick glance, it’s the kind of plant I put into the bucket of “merely ornamental” — pretty but not useful. A shrub with some delicate white flowers. You look nice, but let me get to meeting giant trees holding down entire ecosystems, or finding out more about things I can forage to eat in the woods. Basically I judged an attractive person as unsubstantial and moved on. But turns out Holodiscus discolor is a whole lot more than its little clusters of cute white blossoms.

We had another chance to meet last year, when it was introduced to me by one of its nicknames, oceanspray (sometimes written as two words, ocean spray). That might ring a bell for some of you: yes, it’s the name of the straw bale townhome complex that I wrote about after volunteering at the bale raising last year, and which I just moved into. I had been dubious about the name of the project at first. I mean, isn’t “Oceanspray” a weird name for a spot in a semi-arid climate hours from the coast?

My disdain was linked to ignorance, as I soon learned from the project developer (a serious plant enthusiast), who intentionally chose the name of a plant native to the region, to link it to this place, and not out of any nostalgic feelings toward the ocean. (And certainly not for that other Oceanspray, despite its viral popularity.)

The very name of the townhomes suggests the potential for synchronicity between sustainable-housing development and native plants: “Oceanspray” is the common name for Holodiscus discolor, a shrub found throughout the Pacific Northwest and California in fire-prone environments and described as a “post-fire survivor species,” sprouting from surviving root crowns even after high-severity fire. Like the plant itself, the Oceanspray Townhomes show the potential for growth and adaptation for communities facing wildfire risk.

(In case you’re wondering at this point: the plant is called oceanspray because the flowers look like the spray on the edge of a wave.)

But then a year passed. I hadn’t really been looking for oceanspray, had honestly mostly forgotten about it. But as some of you know, I had to move this last month, and I came to check out the last open unit at the Oceanspray Townhomes. Sitting with the owner on the porch facing the front yard here, I looked at some of the new plantings on the edge of a small swale. I couldn’t see them very well, but could tell that they looked like young shrubs with slightly toothy leaves. They weren’t yet in bloom. “Are those currants?” I asked.

Uh, nope. It was oceanspray, turns out, the plant whose face I clearly hadn’t bothered to keep in my memory, even as I sat there considering moving into the building for which it served as a namesake.

You’d think I would have taken the time then to at last get better acquainted, but I let myself be distracted by discussing lease terms and moving timelines and all those kinds of things we humans have invented to keep ourselves busy and less attentive to knowing some of our plant kin.

We now come to the point in the story where I will meet oceanspray yet again, in a completely new context, and find out that they’re a total badass, and that it’s been to my own detriment that I’ve more or less been ignoring them this whole time.

This is how it happened: this weekend I went on a guided walk of a local restoration project (about which more to come later), where our attention was directed to a small patch of ground, recently burned but green with fresh growth. It was a cultural burn, a couple years out. Its target? A patch of oceanspray, a culturally important plant not just for the Takelma peoples of this area but for many of their and our regional neighbors. Because, as it turns out, plenty of other folks are already more than aware of oceanspray’s many useful attributes.

Here’s just a partial list of some of the groups who did and do make use of oceanspray. On that list are a wide variety of medicinal uses from the seeds, blossoms, and bark — for everything from treatment of burns to alleviation of symptoms from smallpox — and a great array of different tools made from the wood. (Like many a hardwood shrub known for its durability, it makes it on the list of plants sometimes known as ironwood.)

The cultural burning of oceanspray encourages straighter growth of its branches, making them useful for arrows, digging sticks, and more, which is how it was often used in the Southern Oregon and Northern California region. Also popular around here: using the branches as counting sticks for various kinds of gambling games.

Its use in those games might be why oceanspray was also highly associated with luck. There’s a whole bit on this association in the book Ethnobotany of the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Indians, written by Patricia Whereat Phillips, a former Cultural Resources Director for those Confederated Tribes. In a section on spirit powers associated with various plants, she talks about luck powers, which “brought good luck and wealth”:

“Certain individual plants were also luck powers. […]

If a person was lucky enough to encounter a luck power in the form of a bush or tree, its wood would make a very lucky implement in gambling games or sports. Jim Buchanan mentions another plant, “ironwood” (ocean spray, Holodiscus discolor), that could also appear as tłxínxat [that’s Coos Milluk for ‘luck power’]:

“Ironwood was a power, a woman, weeping out in the woods, all decorated. He saw it was a person, he went, 4 times he didn't get to her, the 5th time, scared to death, he gets to the weeping woman. She had a white thing which he took from her nose. Then he fainted, lost consciousness. When he came to she was gone. Neither had spoken. While lying senseless he dreamed. In the dream she told him he would be wealthy. While he lay there it became 2 dentalia. He brought it home, he cached it 5 days in a hole in moss in the ground, and it multiplied. She was ironwood.”1

Got the full picture yet? Oceanspray is Lady Luck herself, and not only can she spread her magic to the next roll of your dice (or shake of the gambling stick), she can turn into an arrow to bring down your prey, or be transformed into a medicine for what ails you. And that’s just what she does for humans; we haven’t even touched on all the roles she plays as a pollinator and habitat provider, in addition to all that “helping the whole landscape recover from wildfire” work.

As I said, oceanspray turns out to be a bit of a badass.

This, friends, is why it’s a good idea to go and meet (really meet!) your plant neighbors, in addition to your human neighbors, wherever you happen to live. Who knows what you might be missing? I certainly didn’t.

But this evening I finally went and said a more proper hello to the oceanspray here on the lot. I have a hunch we’ll be seeing more of one another in the near future.

Who have you met around your neighborhood lately? Any flora or fauna that turned out to be more than you knew at first glance? Always love to hear how others are connecting to the places they call home. Leave a comment or write me at unsettling@substack.com.

Thanks for reading Unsettling. Until next time,

Meg

Buchanan quote from Beckham, Stephen Dow, Kathryn Anne Toepel, and Rick Minor. 1984. Native American Religious Practices and Uses in Western Oregon. University of Oregon Anthropological Papers No. 31. Eugene: University of Oregon Department of Anthropology and Oregon State Museum of Anthropology, cited in Whereat Phillips, Patricia. 2016. Ethnobotany of the Coos, Lower Umpque, and Siuslaw Indians, p.9.