From the Archive: Reenacting Rebellion

On art projects that reinvigorate the imagination toward emancipation

We’re about a month out from the Juneteenth holiday. It’s been a scant three years since the day received official federal recognition, and those three years have seen the advances to truly reckon with our national history attacked or slipping on many fronts; last week brought news of high schools in Virginia reinstating names that honor Confederate generals, reversing decisions made in 2020.

As conversation picks up in the coming weeks about how best to celebrate Juneteenth during this time of backlash, I thought I’d reshare last year’s post from the holiday, as a reminder of the more complicated version of history we might fight to have recognized, and the kinds of projects that might actually help us do so.

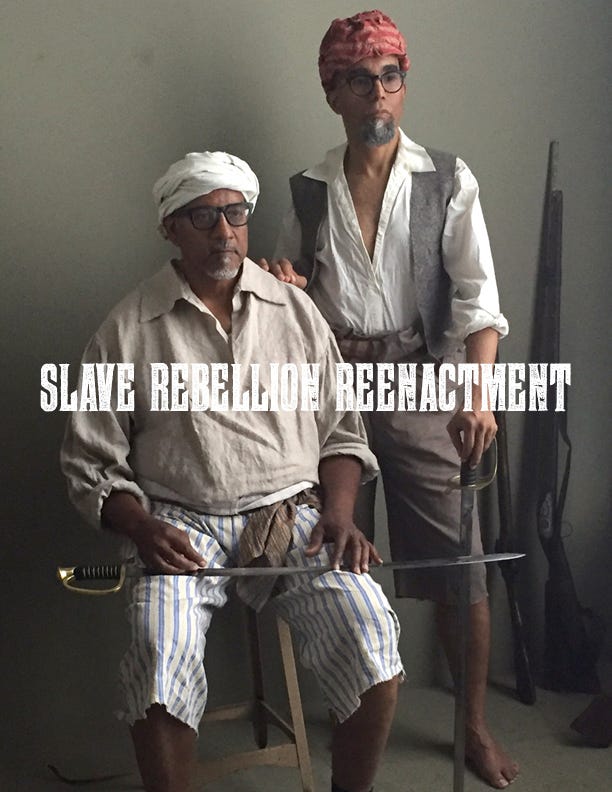

Highlighted below is artist Dread Scott’s 2019 production “Slave Rebellion Reenactment.” Scott has been making headlines again this year with his “All African People’s Consulate” at the Venice Biennale, which challenges racist immigration policies that restrict travel of African people, put in place by the same European countries responsible for colonizing the African continent. The New York Times did a profile of Scott discussing the impact of this project on its participants, and putting the piece in the context of the rest of Scott’s work.

Taken together the consulate and reenactment projects push us to keep reimagining the fight for Black freedom, to broaden our conceptions of how it has been and how it might yet be won.

Hope you enjoy getting to revisit this piece.

As always, thanks for reading Unsettling.

Until next time,

Meg

Juneteenth, Storytelling, and Freedom

Originally published June 18, 2023

Here’s a story, variations of which you may have heard often this week, as we approach June 19th:

It’s summer 1865, more than two years since Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. A Union general makes his way into Galveston, Texas with a company of 2,000 soldiers. Until now, the Union army has had little presence in Texas, and slaveowners have continued holding people in slavery, federal law be damned. But with the arrival of General Gordon Granger, a few months after the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee, the times will finally change. Granger reads aloud General Order Number 3: "The people of Texas are informed that in accordance with a Proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired laborer.” Jubilation breaks out among those newly freed, a jubilation soon to be repeated on the same day each year. This is the origin of Juneteenth, a holiday originating in Texas and now internationally celebrated to commemorate the end of slavery in the United States.

Here’s another story, one I’ll wager most of you have not heard, or certainly not often:

It’s winter in Louisiana, in what many now call Cajun Country. But in 1811 it is known as the German Coast, so-called for the wave of immigrants who arrived in the 1720s. Fifty years before the start of the American Civil War, jurisdiction is muddy here. European powers have tossed ownership back and forth: France, then Spain, then France again. There is already discontent in the air with this game. German immigrants revolt against Spanish rule in 1768; the governor flees. French settlers are participating in the slave trade—and enslaving Indigenous persons who resist the incursion onto their land—and setting up plantations, when France sells the territory to the toddler nation that is the United States. In the very same year France’s colonial project in Haiti is meeting a bloody ending, and some of Haiti’s former sugar plantation owners relocate to Louisiana, transplanting an entire exploitative economy. Yet free Haitians are also moving into New Orleans, complicating enforcement of the racialized order. As do the networks of Maroons living in the swamps, dodging capture and persecution.

It’s here that the largest uprising of enslaved people in the United States takes place, as hundreds of people join in early January to march twenty-some miles over several days towards New Orleans. As they go, they burn the plantations: the houses, the mills, the sugar crops in the fields. Some estimate that as many as 500 people will join the revolt; we know that at least 95 were killed, murdered by militia or executed by officials afterwards. 95, in contrast with just two plantation owners who die at the hands of the rebellion.1

There’s a difference in these two stories, clearly. That difference reveals how there are still ways that we go about telling the story of slavery’s (partial) ending in the Americas that places agency for that ending in somewhat questionable quarters. Does freedom come only when the reach of the military and state grow long enough? Does emancipation really arise from the penning and reading of statements by White leaders to their passive Black listeners?

I don’t believe the intent of tellings of the Juneteenth origin story is that we answer these questions with a “yes.” I do think, however, that when this is the primary and possibly only story we tell as we discuss the holiday, we may unintentionally reproduce an emaciated understanding of how freedom is won—forgetting both the large cast of actors necessary for it to come about, and the staggering challenges they often faced.

Rebels on All Sides

The word ‘rebel’ is often used to discredit those to whom it is applied—especially those not in the official seats of power, or those who have lost. Hence in the context of U.S. history in the era above, we have come to remember the ‘rebels’ as those who fought for the Confederacy.2 There’s an interesting trick at play here in how history gets remembered and told, one that makes us forget that those on the side of justice were also engaged in rebellion, and that it is their acts—prior to the South’s threat to secede—that pushed the nation to a tipping point on the matter of slavery.

We call these prior rebels “abolitionists” now, for their cause that was eventually taken up (whole-heartedly or no) by leaders who happened to win enough elections and who could also command military backing. “Abolitionist” is a useful term, of course, but it slightly obscures how someone like Harriet Tubman was really nothing so slight as what we might today call an activist, but rather someone seriously engaged in rebellion: she helped people defeat the confines of the existing political order through illegal means. She raided and rescued. Eventually she did this for the Union Army, to spectacular result. But before then she was a bandit, defiant of many unjust laws, and not just those in pro-slavery states.

Rebellion is not always for the cause of collective liberation—southern secession in the aim of upholding an extractive, violence-based white supremacist economic system would be the obvious example already in hand. But when that’s the system you’re up against, you don’t get the type of state action written down in the history books—the Lincolns and the Grangers—without rebels like Tubman, or Nat Turner, or the hundreds of unnamed participants in the 1811 German Coast uprising. Such rebellions—even those that fail—are a shout and a cry toward a future that many would not yet dare to dream. But they may and do dream, when roused by those who know that supplications, requests, and slight policy manipulation is no way to win your life back, or the very possibility of life.

That is what we ought to remember, when we hear that Juneteenth origin story brought out yet again without any context as to how abolition was not just popularized but then brought the whole country to a crisis point. It will also help us develop more of an answer to this question we’ve been asking here at Unsettling in recent posts: can rebellion help lead us to repair?

Pro-slavery rebels remind us that the answer must include “no, not always;” but uprisings by those who were enslaved mean we can also answer with, “yes, sometimes, yes.” Sometimes rebellion is very much the needed first step to mending what is broken—especially when that which is broken refuses to be known as such. Rebellion is what makes the rupture in that which, until that moment, is taken as normal and legitimate. It shouts that harm is taking place and that it must stop—the first step in any reparative process.3 And if it’s an act of rebellion as good as, say, Harriet Tubman’s, it actually succeeds in removing real people away from real sources of harm and destruction along the way.

Reenacting Rebellion

If rebellion itself can be repair, can forging connection to rebellions also be reparative?

What do I mean by ‘connection’? Well, learning and thinking about them, as we’re doing in this very moment, could count. But for something much more full-bodied, thorough, and transformative, I can’t think of anything better than the project envisioned and led by social practice artist Dread Scott, bluntly titled “Slave Rebellion Reenactment.”

Scott’s project is why I know anything about the German Coast uprising at all.4 But then he admits that, until the project, he didn’t either; he was initially considering other more well-known rebellions. In the end, in 2019 he and a whole production team recruited, costumed, and walked with hundreds of re-enactors carrying period weaponry along the same route in Louisiana to New Orleans originally covered in the 1811 revolt. There’s great video capturing some of the re-enactment, and reactions from both the crew and spectators, by the The Guardian:

The relevance of the 1811 rebellion is made clear in the simplest of ways by some of those who showed up: both a descendant of one of the original rebels, and relatives of Oscar Grant, attended. The route of the walk is itself the modern descendant of a colonial extractive economy: the plantations have become oil fields, refineries, an area now known as “Cancer Alley.”

What does such a re-enactment really do? As one re-enactor puts it: “Embodying the spirit of freedom and emancipation—that’s really powerful.” Embodied reenactment, not just verbal storytelling, or watching a professional cast capture the movement in a movie—that’s part of what’s key here. It’s how a performance becomes practice, in the sense of training or rehearsing. Practice for being a rebel, or a freedom-fighter.

I recommend watching the video for further understanding the spirit of the reenactment, and I also especially recommend this long profile in Vanity Fair of both Scott and the rebellion reenactment project by writer Julian Lucas. Lucas, wondering if bringing greater visibility to forgotten history such as this will do anything, concludes like this:

There is, of course, a chancy alchemy by which cultural recognition really can change political reality. In June, when a congressional committee met to discuss reparations for slavery, one witness was Coates, whose 2014 essay “The Case for Reparations” brought the question into the political mainstream. The bill they considered cited not only scholarship but “popular culture markers” as evidence of the widely felt need to make amends.

Dread Scott’s Slave Rebellion Reenactment embodies a similar impulse, but the change it envisions is less concerned with society’s top-down moral repair than its radical reconstitution. A chimerical combination of artwork, community organizing, and protest, it resurrects the past to further egalitarian change in the present. What’s singular is that it is neither a solemn penance for American slavery nor a premature commemoration of achieved racial justice. Instead, Scott asks us to look upon an Army of the Enslaved that marched for freedom—against the United States—and celebrate their victory. What else could we imagine if we could imagine that?

There’s a question for us this Juneteenth. Can we really believe in such a desire for freedom? What else can we imagine if we can imagine that?5

“Lost,” yes, though clearly the long social war of those aligned with the Confederacy continues ever on.

This is usually written as “cessation of harm” or “guarantee of non-repetition” in reparations policy language.

Full disclosure: I participated in the 2015 grant-making process for the Fellowship for Socially Engaged Art at A Blade of Grass foundation, which awarded Scott funds for this project.

Myself, given Juneteenth happens during Pride month, I’m imagining what could be opened up in celebrating not through parades but—taking a cue from Scott—reenactments. Would our ability to stand up to police violence increase if Pride routinely saw us reenacting Stonewall?