Border (Dis)Orientation

A hike to the local borderline and some fun with maps

When I try to tell people about where I live, I often resort to mentioning the proximity of the nearby state border. For instance, I might try to explain to some East Coast friends that just because I live in Oregon does not mean that I am right next to Portland (commonly their main association with the state), a point I might make by stressing that I can walk to the California border.

Which I did, actually, on my first backpacking trip here the same month that I arrived, as a way of orienting myself. I walked to the California border and back, in a semi-loop allowing me to circumnavigate the watershed providing the local drinking water supply. Taking 4 days and covering over 70 miles, it’s not most people’s idea of a “walk,” but I did it in part to prove a point: I can get to California, from my front door, by foot.

The sign above is what you’ll find if you take the same route, via the Pacific Crest Trail. My own dedication to touching the border at this particular spot has to do with missing it a bit over eight years ago: I stopped my first big PCT hike 50 miles shy of here, sick from exposure to wildfire smoke pouring down from Crater Lake. I ended up recuperating with friends of friends here in the Rogue Valley, the initial prelude to my presence here now.

There’s a trail register there, which I signed this July, experiencing a momentary sense of completion before immediately turning around and marching quickly back up the same hill I’d just hiked down to flee a gathering crowd of mosquitos. Nice to see you, California. Gotta run.

More recently, as I’ve begun the work of trying to learn more properly just where it is I am, I realized the silliness of this particular border-touching obsession. Long-time readers of Unsettling will remember some early posts in a series I called “Borderline Histories,” all attempts at de-naturalizing those lines on the maps we now take for granted. That borders are constructed and contested, often defined and defended by force, is a thing most of us don’t need reminding of just now with the daily headlines coming out of Gaza. Even then, it’s still so easy to take those lines on the map for granted. But there are some especially good reasons for not seeing this particular borderline only in its contemporary guise.

Let’s start off with the fact that, at one point in time, this was the U.S.-Mexico border. In a slightly different outcome to historical events, it might have been possible to say that one lived in the Pacific Northwest and at the Mexico border, two cultural associations that don’t necessarily blend together in the modern imagination. Here’s a map of the provinces and territories marked in Mexico’s first constitution, just after its independence from Spain, with the leftmost half of that top line encompassing what is now thought of as Oregon’s southern border.

This is a couple decades before the Mexican-American war, when the young U.S. government went (even more) gung-ho on manifest destiny and the militarism needed to achieve it.

There’s plenty to observe about this initial map of Mexico. Shall we point out that Texas, too, is still part of Mexico at this time? But the piece I can’t get over is that long straight line at the top. Talk about something that look likes someone came in and made a big SWOOP with a pen across some paper without ever stepping outside onto the actual land. Where did that line come from, anyway?

Well, more or less from someone going SWOOP with a pen, though after a whole lot of talking. That particular border was set after the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819, one of those documents resulting from various European powers meeting up to duke it out over who got what, without anyone whose lands they were stealing present to dispute the divvying up. Claims to various pieces of territory were made on the basis of who said they’d explored somewhere first or most thoroughly. That no one was thorough is obvious in that line: it’s squiggly on the right side of the map, where there was some real knowledge of the major rivers by all parties. Where there wasn’t, they resorted to lines of latitude and longitude. SWOOP.1

In contrast, here’s the map of territory claimed by what was then “New Spain,” before 1819:

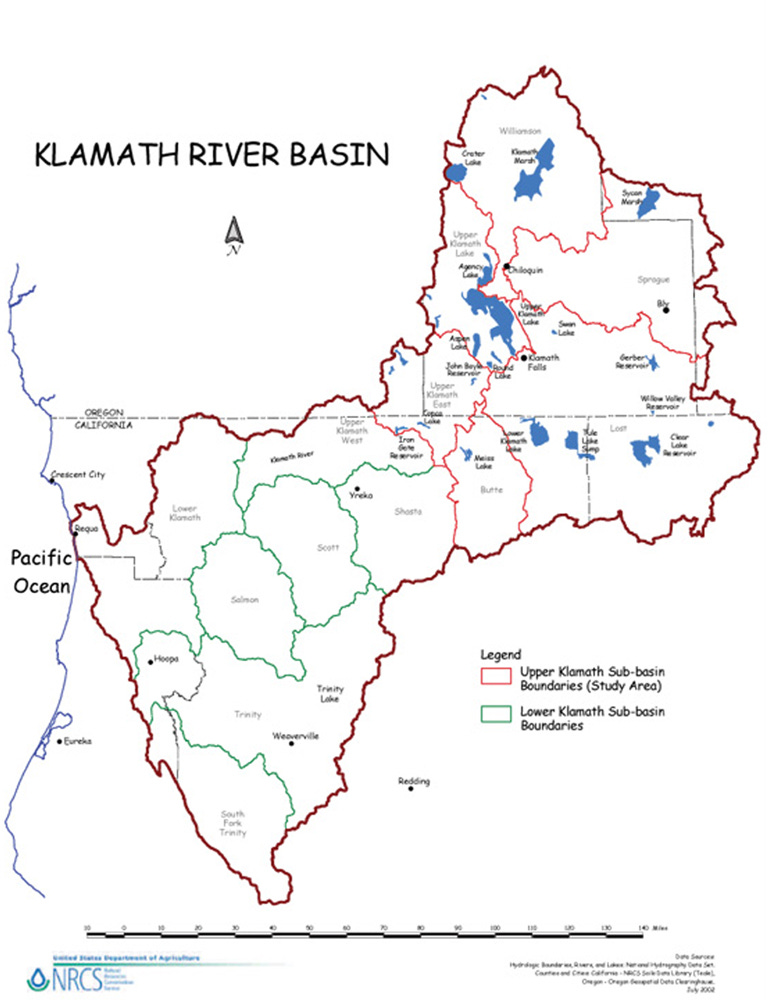

The wiggly lines are all water. In this version, the northernmost boundary of New Spain near the Pacific coast — still a little hazy at its start — looks like it then aligns roughly with the northern edge of the watershed of the Klamath River, whose shape you can see here:

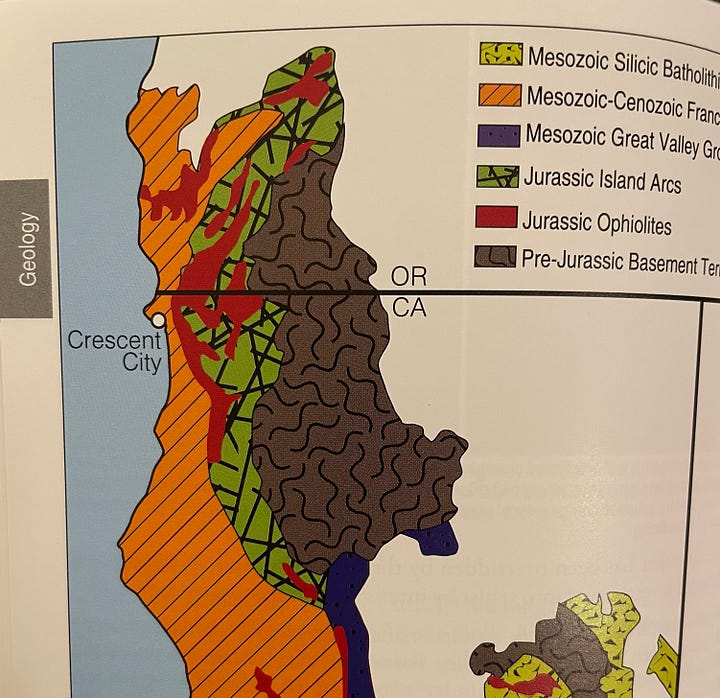

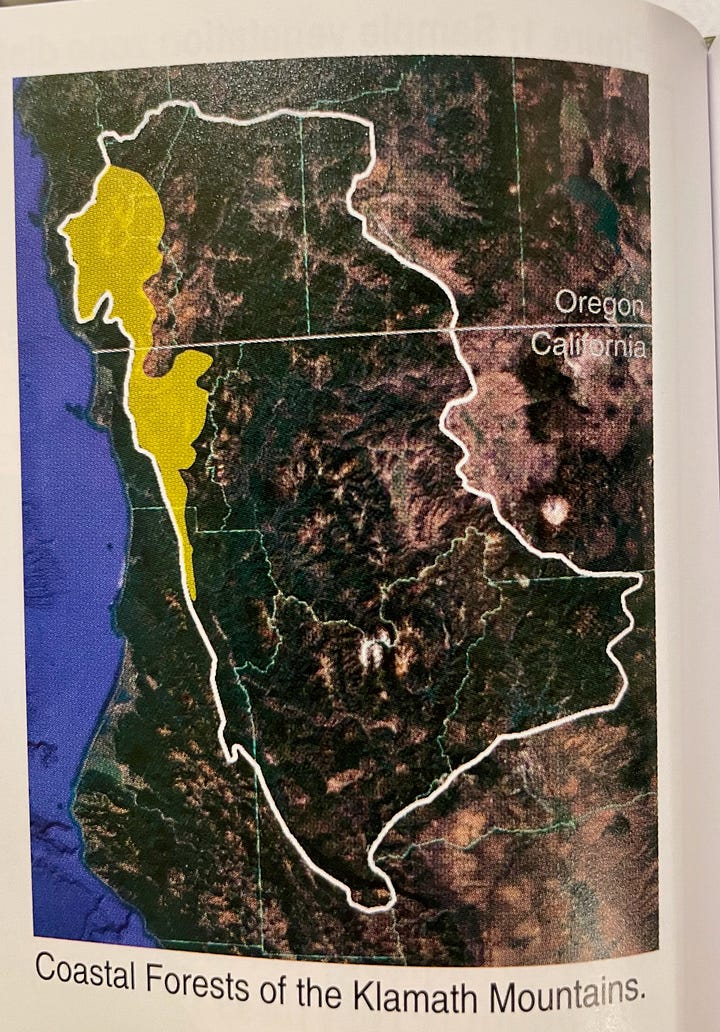

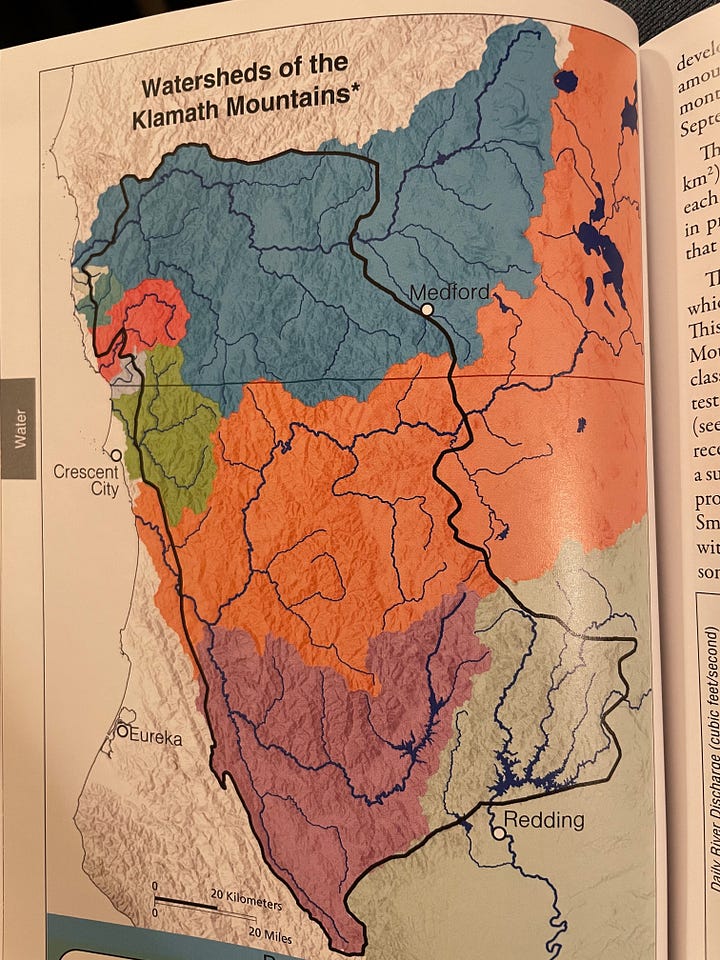

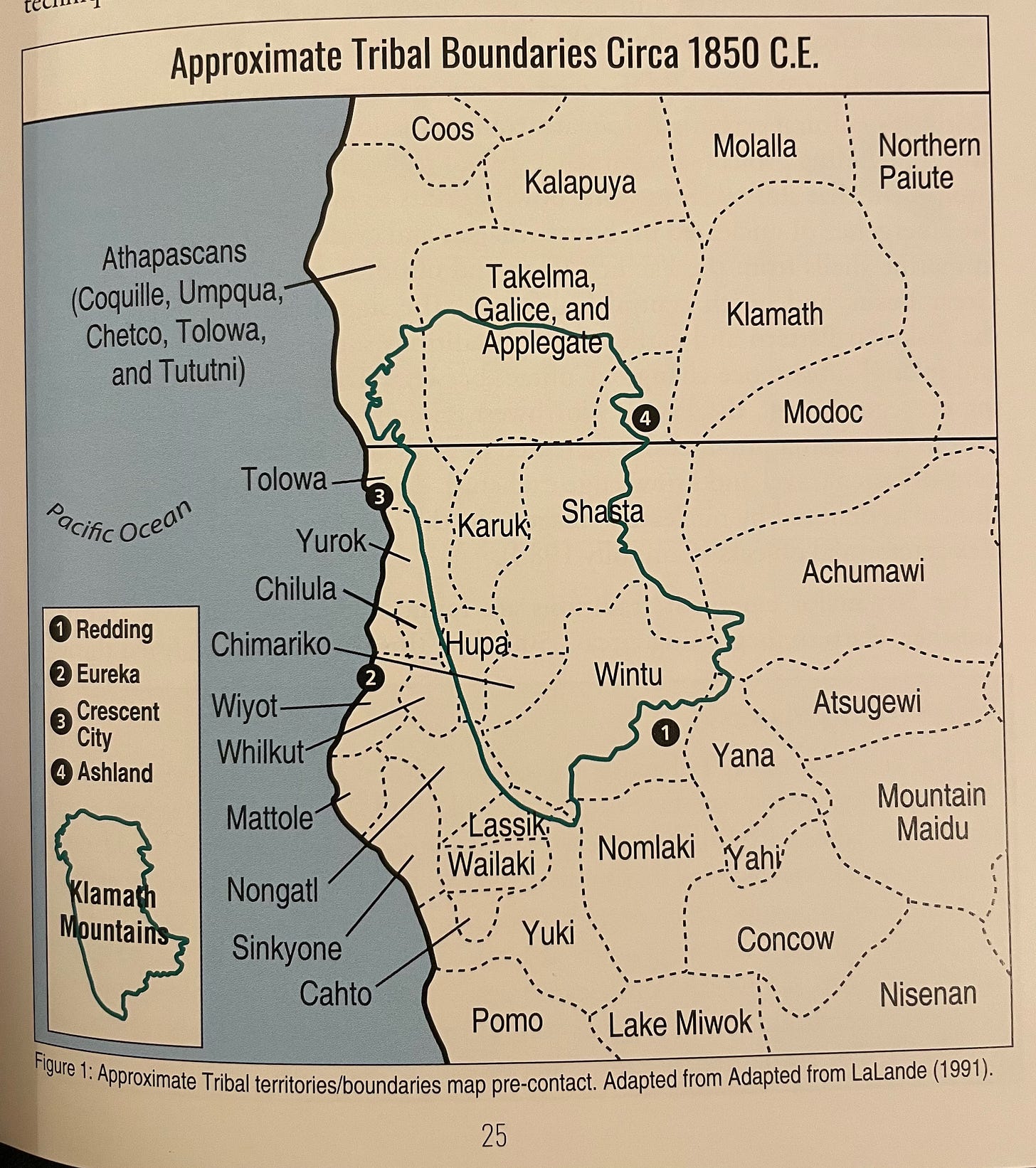

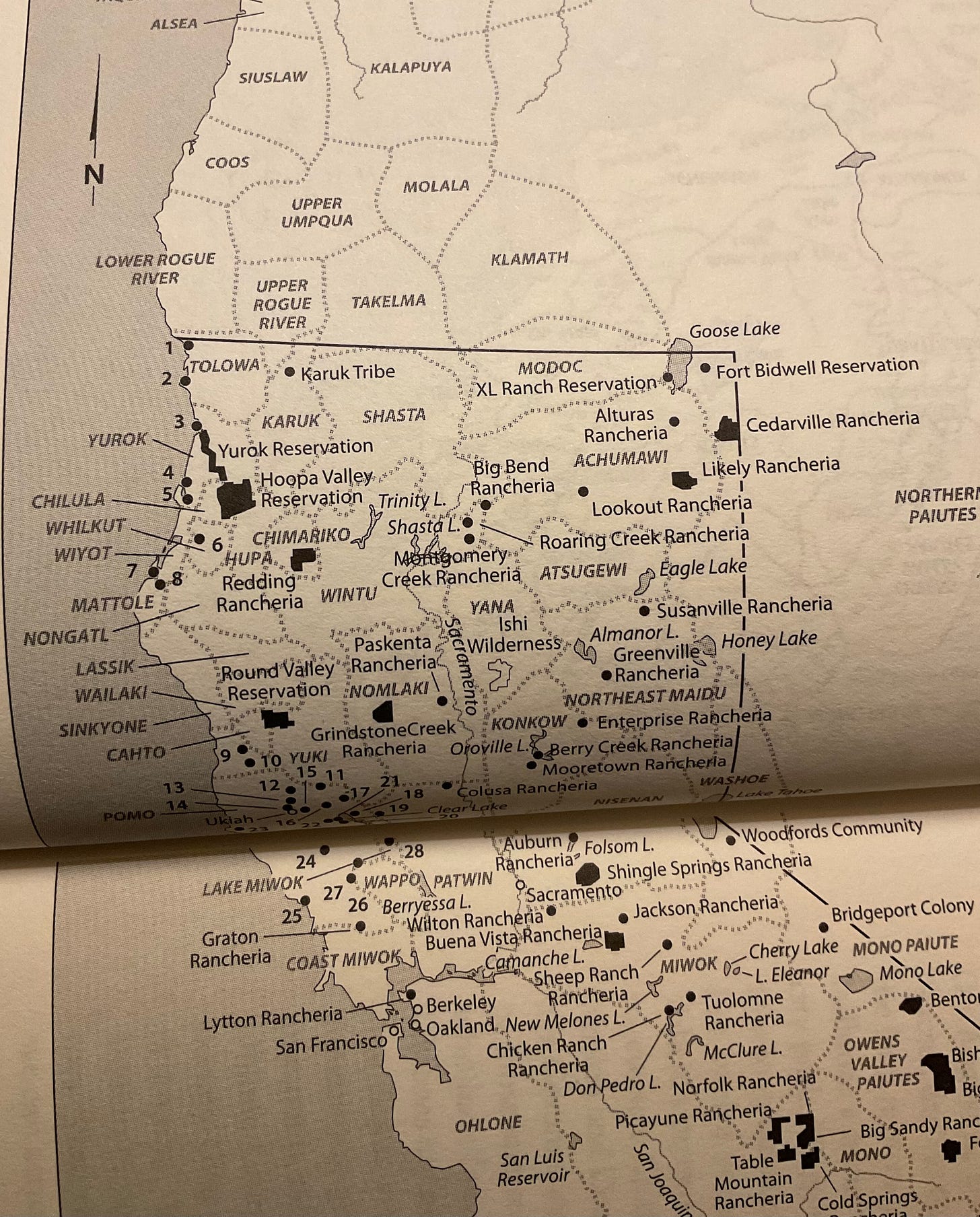

That’s a pretty darn sensible feature, around here, to base one’s map upon. The 42nd parallel, on the other hand, has a tendency to bisect just about every natural and social community in the region. Whether it’s people, or rocks or trees or creatures, all tend to group in ways that specifically jump across the current borderline. And there’s a real reason for that spread: the Klamath Mountains stretch right across, at a sort of diagonal tilt from northwest to southeast, greatly influencing the movement of anything living in this area.

One recent book on the region, The Klamath Mountains: A Natural History, is full of maps of natural features as well as the distribution of various plant and animal communities, all with a superimposed outline of the mountain range, making the oddity of that straight border more than evident:

The parallel likewise cut across the existing social communities at the time it was chosen as the borderline:

Here’s how that maps onto land claimed by Tribal communities today:

State borders are always a little artificial, but the manner in which the 42nd parallel unnecessarily cuts through and divides so many small and unique communities makes it especially so.

Yet we use artificial lines such as this one to shape many of our own conceptions about what a place is like. Our tiresome Red State/Blue State divide in popular discourse is just one example (and a distinction that happens to be quite unhelpful in these particular parts of these two particular states). The more we let the unexamined categories resulting from borderlines harden, the more we let the powerbrokers of the past with their pens and maps continue to have excessive and arbitrary sway over our future. Do we really want that?

An alternative might be to look to the lands where we are and try better to understand the communities rising from that place itself — ones that often span both sides of modern borderlines. There’s the subtle beginnings of transformation in such reconceivings, the potential to remap identities and allegiances and more.

So what does it mean that I went and touched the border on my hike? It means I chose an arbitrary marker to give meaning to my journey, gaining a little motivational juice by having a clear destination. I know now, though, that there was a better halfway point for that trip, had I let the Klamaths themselves offer it up rather than staying dedicated to the mark on my map. I hit it a few miles before the trail register (and hence before the mosquito swarm, had I only known!) There, the trail zigs across and over a ridgeline, and serves up a view of the many valleys running south and west toward the coastal forests.

If you pause there on the saddle, as I did on my return, you’ll find it a perfect place to take in the sunset and watch all the mountains melt into the twilight blue. It’s a place to take in the decidedly tumultuous shape of this land, so unlike any set of pen-forged parallel lines. Somewhere that feels very much like a middle, rather than an edge — not a border but a heart.

Thanks for reading Unsettling.

Until next time,

Meg

There really wasn’t knowledge. Surveying wouldn’t happen until much later, in the 1850s, after the 42nd parallel was again upheld as the border of California in treaties signed after the Mexican-American War.