From the Archive: Getting Over Guthrie

On releasing attachment to a cultural touchstone

As we’re nearing the big national holiday of the summer, I thought it appropriate to republish the essay on the song “This Land” from last year. It’s one of the earlier pieces I wrote for Unsettling, and as we’ve had lots of new folks sign up since then, it’s likely that many of you have not read it.

Over Memorial Day, I attended a Pete Seeger sing-along in which “This Land” was the closing number. I walked out, and later, had a brief but interesting conversation with the one musician in the group who also clearly opted out and sat offstage for the song. I hope to write about that conversation soon, and the original essay here is a useful preliminary.

I’d also love to hear from subscribers in the comments: are there any cultural items that you once held dear which you’ve learned to let go? You’ve got a minute to think about it—I’m still out hiking for another week at least. Hoping to read your responses when I return!

Until then,

Meg

If you’ve read Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, you know the full catalog of terror it documents. Heartbreak follows upon outrage, one gut punch after another. Genocide in myriad forms is foundational to U.S. history, and Dunbar-Ortiz strives to give us a crisp picture of that reality. Not in the fashion of “let us cry in remembrance,” but in a way meant to make clear all the connections between present and past, and to highlight that how we talk about the stories of the past can be as important as the content of the stories themselves. As she says, “Awareness of the settler-colonialist context of U.S. history writing is essential if one is to avoid the laziness of the default position and the trap of a mythological unconscious belief in manifest destiny.”

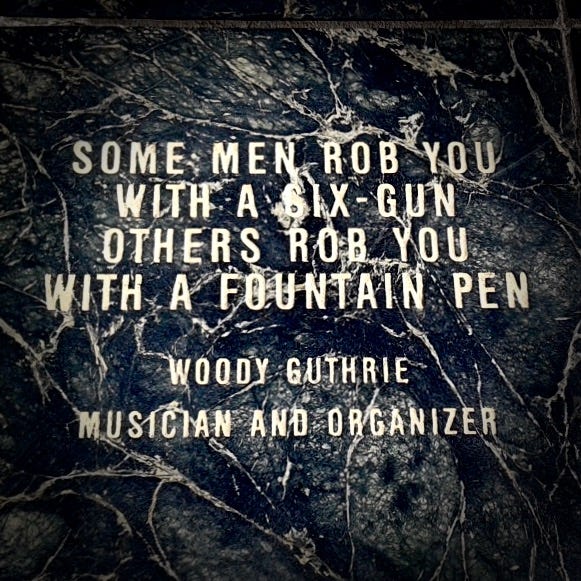

Yet I was caught off guard with one of her first examples of that “unconscious belief.” It’s a quick reference, the first sentence in a cascade of paragraphs in the book’s introduction giving an overview of the policies, historical moments, and dominant narratives that constituted settler colonialism in the early U.S. All she says is this: “Woody Guthrie’s “This Land is Your Land” celebrates that the land belongs to everyone, reflecting the unconscious manifest destiny we live with.“

Woody Guthrie? I remember pausing, doubling back. There it was—Woody Guthrie, working class folk hero—named as a perpetrator of the murderous vision of Andrew Jackson. The idea hurt a lot more than I would have imagined. If I had been honest at that moment, there was an argument happening in my head. “Yes, literally the words are about the land, but isn’t it clear that this is about making room for the poor and destitute?” “Clearly this is not about the mass displacements that happened in the U.S., but can’t we agree that not every piece of art needs to address every issue?”

At the time, I didn’t really dig into the why of this defensiveness. Reading even a few more pages into Dunbar-Ortiz’s book, as it dove into the particularities of the United States’ campaigns of physical and cultural genocide, was enough to make it clear that giving up attachment to a song was relatively little to ask in the face of the suffering that others had experienced and which they associated with the song.

Only a few weeks ago, however, such attachments and defensiveness were on full display after Jennifer Lopez’s performance of “This Land” at the presidential inauguration. Which made me think maybe it was finally time to examine my own sense of connection to the song, where it had come from, and why it was difficult to let it go.

If you had asked me during college to define community organizing, I probably would have given you a blank look. Funny, for someone who now thinks of themselves as an organizer, but my general politicization didn’t happen until after college. And at that time, one thin, glasses-wearing, guitar-playing, and labor-ballad-singing graduate student and organizer played quite a role. We met, I think, at a film series that was to be my introduction to how little I still knew about the world, even after four years at an esteemed liberal arts and research institution. I still lived near and worked for the library at the university, and the series, Labor, Globalization and the New Society, was put on by the student film society. It featured films like The Corporation, Bread and Roses, and The Take. Hanging around after many of the films was Joe, trying to engage others in conversation and pull them into any number of local organizing efforts, including one for greater democracy and transparency within the very union of which I was a member as part of the library staff. It was through him that I would attend my first ever organizing training at the now defunct New World Resource Center in Chicago. Sponsored by the IWW, it opened the door for me to learn about the radical labor tradition in Chicago, which would become one of the strands most strongly influencing my own work as an organizer.

My labor history at the time was pretty thin; it would still be another year or two before I began reading works like Howard Zinn’s A People’s History. But my curiosity was certainly sparked. As I learned more, I began to feel, for the first time ever, connected to the history of where I lived, in large part because of those who had worked to change it for the better. I would look at a map of Chicago or walk its streets and see the sights of its past struggles. I could visit the site of the Haymarket massacre, which led to the establishment of May Day, or the historic core of Pullman, and learn about the country’s first all-black union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. I might be dismayed as I learned about the brutality visited upon those working for economic equality during the first Red Scare of World War I, but I could sell myself a narrative of at least some incremental progress: eight-hour work days, child labor laws, integrated unions and greater civil rights, and the very right to organize against exploitation of working conditions.

I could learn about all this, and it began to help form a growing sense of purpose and a sense of being placed, both physically and historically. And what’s more, I could sing about it.

The civil rights movement is known for having music at its core, but so were the earlier unions of workers. Both of these fed into the folk revival in the United States. The folk revival—if you’re unfamiliar with this, you can think about it as the phenomenon that gave us Bob Dylan—drew lots of inspiration from the earlier labor music tradition. Not just its tunes, but tunes about the tunesters. Joan Baez, Phil Ochs and many more would go on to sing a song first made famous by Paul Robeson, “The Ballad of Joe Hill.” Said Joe Hill was the author of many songs to be found in the Little Red Songbook, the Wobblies’ own printed collection of music.

For a person whose youth and young adulthood involved church as a central activity, singing was a key way of being in community and connecting with others. I’d also had some magical summers at Girl Scout camps, and fond memories of songs before meals, songs as the sun went down, songs as you hiked through the darkening woods and tucked into your cabin for the night. I’ve very limited vocal ability myself, but in these communal contexts, it didn’t matter much. The point was, as they say, to make a joyful noise.

So a communal singing tradition was helpful in making the transition, as I was at this time, away from one set of institutions and relationships into another. All these old folk and labor songs seemed to connect everything together: artists I’d heard on LPs on my parents’ turn-table; my whole new sense of the community of struggle; other forms of folk music I was finding I loved—I attended or volunteered for the annual folk festival on campus all seven years I lived in the neighborhood—all this could come meeting together in some faltering attempt to sing “Solidarity Forever” at the end of a gathering. (The UofC Folk Fest, which was intended in part to help new fans of Dylan et al. to understand the roots and origins of where that music was coming from, happens to be streaming online this year, this upcoming Friday and Saturday.)

There in the swirl of all of this, of course, was Woody Guthrie. I remember feeling delighted to discover that this purportedly bland song of my childhood—I could picture sitting on the carpeted classroom floor as an eight-year-old, in a circle with other children, singing “This Land”—had other verses, that were not so dull. Here, in fact, was a song by someone that seemed more like my family than most folks I knew: itinerant white working poor, moving about the West in search of some form of work and lodging that might last, and finding that goal a fair amount more difficult than it seemed it ought to be.

In the shadow of the steeple, I see my people

By the relief office I see my people

As I stood there hungry, I stood there asking

Is this land made for you and me?

The last line of that verse always hit home for me. It turned out it was a question I had been asking my entire life, unsure of its answer. Only now I was not asking it alone, but with others who had also grown up watching their parents work crap jobs, or working them oneself; people whose families had maybe survived in lean times on food boxes from the local church food bank; people whose experience of housing instability meant never knowing quite how to answer the question “where are you from?”

This land. Maybe we could just be from “this land”?

Some of the old Wobbly tunes were, to be honest, difficult to sing in groups made up of folks with limited experience in group singing. But “This Land”? Just about anyone could handle that, because we knew it, in the way you only know songs you learn as a child. Such songs live inside in an unmarked place, and you forget about them until it’s time to sing and you don’t have to struggle to remember the words or the melody. Such songs give comfort, and a sense of groundedness, at the same time as they deliver hope and a sense of possibility. And that is what, for a time, “This Land” and Woody Guthrie meant for me.

I can feel all that again, thinking back to those years in my early twenties. My whole understanding of the world was being torn apart, but it felt like I was landing somewhere solid in the midst of it all. Not so long after that film series on globalization, Joe and I would be among the founding members of a union that would win massive pay increases for teaching assistants at the end of our first year of organizing work. I wasn’t just learning about the history of fights for better working conditions; I was a part of making it.

It’s almost enough to make me want to argue about the song again. But then I try to imagine singing it with any Native folks I know. I can’t.

You try it. Try making it through even just the first line—“this land is your land, this land is my land”—as you imagine looking in the eyes of someone whose family might have been marched off their land at gunpoint.

The words choke in the throat.

I can remember the first time I had the chance to sing “This Land” after reading An Indigenous People’s History, and felt those words stick, unable to come out.

My partner and I had purchased tickets to take my mother to see Arlo Guthrie, son of Woody, on the anniversary tour of “Alice’s Restaurant”. My mom was the reason I knew that lengthy comic anti-war song, and the show seemed like a good opportunity to do something nice for her and share some time together. We were enjoying ourselves, underwhelming though the performance was. It turns out some people really can ride the coattails of one or two single hits for the rest of their life. The juice from his own songs didn’t even quite get him through the evening, as Arlo opted to draw on the family legacy to close out the night: the show finished with a sing-along to “This Land.”

I sat there in the dark with my mouth awkwardly gaping open silently, then closing shut, again and again, as I stared at the concert-goers around me happily singing along. The display over the stage at Seattle’s Moore Theatre displayed American flags in red, white, and blue LEDs. If I had needed Dunbar-Ortiz’s point driven home, there it was: “This Land” and the casual, easy nationalism of the aging boomer middle class fused together in the finale to an evening of musical mediocrity. Sure, I could argue that “This Land” had meanings that weren’t about simplistic flag-waving patriotism, but I could no longer deny its somewhat too-easy co-existence with symbols of expansive American state power.

Making our way towards the theater’s exits, we were caught in the crowd behind an older couple as they gushed enthusiastically about the whole evening. Trying to avoid stepping on their heels, I heard their enthusiasm turn to critique, though not about Guthrie. “If young people today only had good political music like that,” one of them was saying, “they would be out in the streets more, actually doing something.” The other agreed; the youth these days were apathetic at best, and the lack of meaningful music certainly played a role. They were both shaking their heads in studied disappointment.

It wasn’t the first time I’d heard nostalgia for the 60s-era social movements turn into blame toward younger generations. In that moment, though, I saw more clearly how much active ignorance was at play in this game intended to shore up a few individuals’ sense of self-righteousness. There they were, about to step onto 2nd Avenue, only a few minutes from the very section of that street routinely targeted for shut-downs by climate activists (the regional headquarters for JP Morgan Chase, world leader in funding fossil fuel extraction, is the draw here), yet lamenting “the absence of young people in the streets.” Furthermore, not even a year had passed since Kendrick Lamar had received nothing less than a Pulitzer Prize, and somehow they felt comfortable dismissing modern popular music as selfish, unsophisticated, and apolitical. I was ready to interrupt their conversation and offer a list of indie rock and hip-hop acts whose lyrics deftly touch on the complicated nature of today’s political situation when I realized I had no idea if I was still near my mom and partner or if I had lost them in the mass of people behind me, and I turned around to look for them.

While it rankled me, the attitude of these Guthrie fans is nonetheless instructive in the matter of how nostalgia for past forms of political change can become not only stale but harmful, impeding new efforts to build a more just world. How can you support young people’s efforts for change if you can’t even see them, bound by attachment to how things were done in your own youth? It also made me wonder further about the “you” and “your” of “This Land.” The song is used—especially as it was performed at both the Obama and Biden inaugurations—to showcase glossy images of diversity, and encourage some continuing version of the melting pot myth. But the entire melting pot ethos has been forged to the detriment of indigenous cultural practices that are dependent on a connection with the very land to which everyone else is laying claim. As that couple at the concert sang it, does Guthrie’s “you and me” include those in the streets protesting police brutality, or indigenous activists seeking return of ancestral lands? From my vantage point in that moment, it didn’t feel like it. And for others listening to J.Lo on January 20th, it didn’t feel like it either.

It’s notable that Dunbar-Ortiz doesn’t say that “This Land” reflects the policy or doctrine of manifest destiny. She specifically uses the phrase “unconscious manifest destiny” [emphasis mine]. What we’re talking about, then, is the long-term outcome, the cultural legacy, of those earlier policies. It is not just the tune itself that lives in some unmarked place, easily and unconsciously sung with some sense of heritage. It’s the entitlement embedded within it, that sense of ownership. That willingness to look at everything around oneself and say “mine”.

Ownership and belonging are not the same, and undoing the confusion between these two concepts is a necessary and urgent task for our time. As others have said, “Decolonization in many ways is an inversion: land does not belong to us; rather, we belong to it.”[1] As long as we continue to emphasize the ways in which we can own some piece of the world, we will continue to fail at determining the new forms that allow so many more of us to belong to it. From this perspective, too, we ought to question whether “This Land” is an appropriate anthem for our age.

I think it may still be possible to laud the intent of Woody Guthrie’s song, its aim of broadening the promise of prosperity to the poor and disenfranchised. But its impact, taking place within a system that actively dispossessed so many from the land to which they belong, is different. Yes, “This Land” might have helped me feel more connected to broader struggles for justice, in a way that overlapped with other parts of my own personal history, at a given point in my life. Was that the only way all that could have happened? Might there be other ways, other songs, to forge such connections, especially for current generations? Songs that don’t call upon or shore up an entire history of white settlers claiming ownership over land as they remove others from it? If you’re like me, angrily brainstorming bands and songs behind that couple at the concert, you probably already have some in mind.

Changing our attachments is hard, though. I can’t grow up again; I can’t learn new music that will resonate in that same, unconscious way. But I’m not the only one that matters, and while my own youth is largely behind me, other people grow up every day. Now is the moment to forge new traditions that—far from forcing young folks into the same forms and practices that only partially served us in the past—will help each passing generation take us further along the path toward a better world for all.

“This Land” may have had a role to play in social and cultural movements of the twentieth century. There are millions of good songs out in the world, though, and it’s time to lay this one to rest and pick a new one for our collective moments, whether big or small. My hope is that the next time a presidential inauguration rolls around, enough of us will have likewise gotten over Guthrie, and that we won’t be treated to yet another “This Land” rendition or mashup.

Maybe by then we’ll also have a few more things we’ve learned about belonging to the land, rather than merely owning it. But we can at least start by letting go of a song.

Notes

[1] Syed Khalid Hussan, from the “Waves of Resistance Roundtable” in Harsha Walia’s Undoing Border Imperialism.

You might also like: