June 1st: the official start of the local fire season. By June 2nd, a grass fire sprang up near town (quickly and easily put out). That same weekend, smoke from fires in the northern half of Turtle Island began traveling south, drifting into cities around the Great Lakes. The power to deny that we’re in for a hot and smoky summer is surely being extinguished by the incoming evidence.

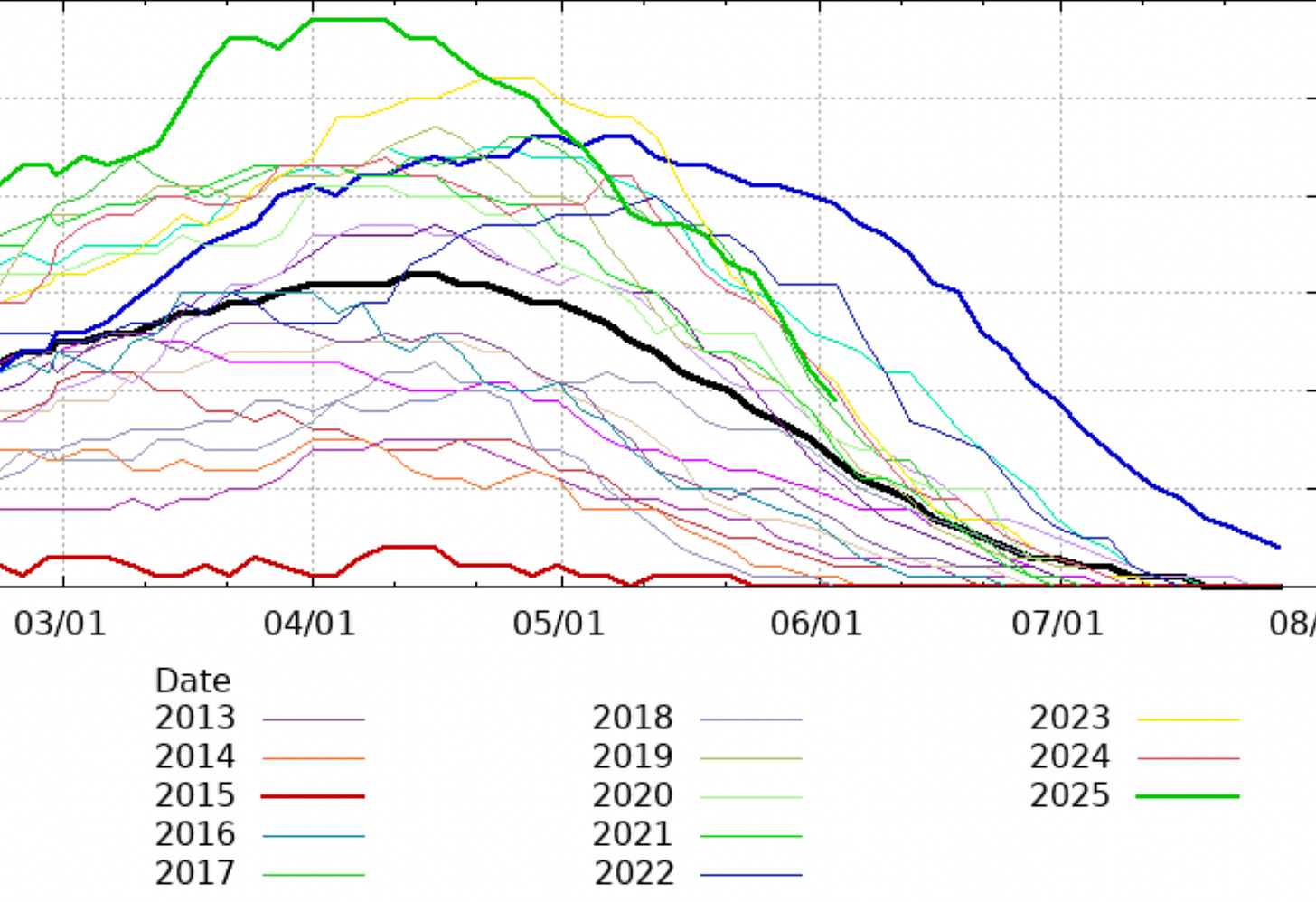

As some friends know, I have my own unorthodox approach to forecasting the potential severity of fire season: I use the charts at postholer.com, which compare snow levels on the Pacific Crest Trail each year. I've logged enough time on that trail in the last decade — sometimes dodging new fires or canceling trips because of them — that I have a sense of the real world conditions the lines on those charts represent.

The line that always matters most, to me, is the one for 2015.

That would be the red line snaking low across the bottom:

2015 happens to be the year I did my first long hike on the trail. It is also, as you can see, the driest year by far.

It was the first year that PCT thru-hikers really had to reckon more seriously with both drought and the force of wildfire. Once reliable water sources in the desert sections were gone. Hikers who made it through that would find themselves later being evacuated from fires around Oregon. Long stretches of trail in Washington closed. High up in the Trinity Alps in California, breathing in what the winds blew down, I grew sick from smoke exposure and had to bail, hitching my way out of the mountains. That little red line marking 2015? It stands in for all of that.

Every year, I am thankful when the bright green line, marking the present year’s precipitation, stays above that red line at the bottom before mid-summer. But here is a snapshot of where we happen to be this year, in California’s High Sierra and the Central Cascades here in Oregon:

In California the green and red have already converged, and we can presume streams will dry out early in the summer.

In Oregon, where we began with a whole lot more snow — it was a banner winter for skiing — the sharp drop reflects a new trend of faster melting in the spring. We have full reservoirs around here, even as other parts of the state dip into drought. But that rapid melt-off means plenty of understory growth that will then quickly dry out if the hot weather causing all that melting continues, as is expected.

(Washington, if you’re wondering, is also seeing below average snow levels but not nearly as fast a decline during the spring months.)

What do you do with information like this? For it forebodes a heavy fire season for the region, if not locally, and it surely means a summer full of smoke. If you’re me, you use it as motivation to squeeze all the season’s backpacking in early, between now and the July 4th holiday, when misguided nationalistic displays inevitably start the fires they quite obviously could be expected to start.

But I also know that these weeks in June, and those short gifts of time in the mountains, are important for preparing, mentally and more practically, and for helping others do the same. Because if I’m honest with myself, the situation heading into this summer is giving off some real 2020 vibes.

Now granted, in 2020 Oregon actually declared its fire season months early, in March. This year that’s not the case. But we are going into the summer with gutted and uncoordinated federal agencies, including those responsible for disaster response. There’s a new, more contagious variant of COVID-19 on the horizon, at the same time that access to vaccines is being made more difficult and millions stand to lose their health insurance. And political repression continues to ramp up as ICE grows more brazen in its tactics, not just in its targets and deportation tactics but in its open aggressiveness in more public spaces — take the raid last week at a San Diego restaurant during its peak dinner hours, in which ICE agents used flash bangs on diners. The economic uncertainty of that first pandemic year likewise finds its echo in the volatility introduced at the federal level.

So yes, 2020 vibes.

Many of us, in response to all that came at us in 2020, did a lot of waiting. We waited for news of variants and case counts, waited for news about changes in risk levels and precautions. We waited for the potential end of a presidency. Some understood that all this time used for waiting could be used for action, and stepped into the movements that expanded after George Floyd’s murder. But even between days in the street there was more waiting, especially once wildfire season came in full force and the smoke chased many inside.

All that waiting happened in part because many of us were unclear about what role we could possibly play in changing any of those particular circumstances, and in part because there was a sense that the moment in time would pass — that it was outside the usual patterns, and that eventually we would move on to what came next, to something more like what we had known before. Many, too many, waited for “a return to normal” they thought would soon come.

Some of us got back to something that approaches the normal we had before. Many of us never did. But regardless of where you sit on that spectrum, the truth is this: the current and coming disruptions — political, social, and in the global climate — are not things that can just be waited through. There is no “return to normal” on the other side. There are only major changes in patterns. Those changes may in some ways resemble the past patterns we have known, but they are also fundamentally altered.

This, too, is part of what staring at these snow charts every winter has shown me. Look at that 2025 curve for Oregon: it has an entirely different shape than in years past. Many of the years in the recent decade show this new shape, the increasingly sharp angle representing more rapid snowmelt in spring because of hotter temperatures. I don’t believe that curve will ever again approach what was “normal” for the first half of my life. It may lose its severity, but it will stay forever changed as a result of all the havoc wrought on our climate.

Again, what do we do with this knowledge? We can’t just escape to the mountains — another form of trying to wait it out.

But here’s something useful: just like I know something about the shape of a coming fire season from becoming familiar with these charts and the terrain they represent, so we have begun to be more familiar with the shape and flow of disaster — the kind of harm that can come, and how it can be lessened. And we know that the first and most important response always comes from community, from the frontlines of those in the eye of the storm. From Katrina to Sandy to Maria. From Palisades to Alameda to Altadena. We save the people and places we love because we save them.

So here is what we can do, rather than just attempt to wait out a smokey and politically unsettling summer: we can get ready.

We can create space to feel and then release the anxiety and fear that come after reading about current and future disasters, that have come from months of reading frightening and frustrating headlines.

We can make sure we have our own ducks in a row: go bags, mask stash, etc. And we can begin getting ready to help others with whatever may come.

We can get organized. We can get in formation. Yes, that is also intended as a Beyoncé reference. Remember that she dropped that transformative piece of art the year that Trump first ran, claiming, rather than ceding, a vast stretch of the cultural terrain, and priming the imagination of millions for the rebellions of 2020.

What does it look like to be in formation? Again, we already know so much more about the shape of what can come, and the shape of what a response can look like. The mutual aid movement continues to grow in leaps and bounds. In posts earlier this year, we linked to the Mutual Aid 101 webinar series run by Shareable as an intro resource. That series has concluded and been transformed into a detailed toolkit for running mutual aid projects. From group process to legal structure to incorporating solidarity economy tools into a project, there’s a lot of good material in there.

If that feels overwhelming, consider that you can accomplish a lot just by gathering with a couple other friends and talking through what you might do, and how you can help one another, if things get really rough — a big fire in your town, another pandemic. Just in doing that you can fulfill one of the most basic goals of mutual aid: to not bear the weight of system-wide failures alone.

I certainly hope my creeping sense that “disaster summer” might be an apt label for the coming months proves incorrect. But I don’t intend to wait and find out. I’ve already begun reaching out to those who helped take on key roles in the community response to the 2020 fires here, to start a conversation about what we might do together.

Do I know yet exactly what that will look like? No. But the point is just to start. Because now is not the time for waiting, but a time to be in motion, and in movement together.

Thanks for reading Unsettling.

Until next time,

Meg